You just finished a beautiful floating dock. Six months later, the frame is rusting, the welds are cracking, and the owner is furious. This is not a design failure. It is a material failure. I have seen too many projects use cheap, inland-grade steel for a marine project. The water always wins. Your dock’s strength and longevity are decided before the first weld is even made, by the steel you choose.

Steel requirements for floating dock construction demand marine-grade materials with high corrosion resistance, such as galvanized steel, aluminum, or specially coated structural sections. The frame must use robust sections like marine angle steel or bulb flats for stiffness, and all connections must be designed for constant flexing and wet-dry cycles, not just static loads. Proper fabrication and protection are non-negotiable.

Building a dock that lasts is more than just buying steel and welding it together. You need to navigate a web of rules, calculate precise buoyancy, handle government paperwork, and select the right materials. Let’s start with the rulebook that governs the electrical heart of your dock.

What is the NEC code for docks1?

Imagine a dock with beautiful lighting and convenient power outlets. Now imagine a child swimming near a dock with a faulty electrical connection. The difference is code compliance. Electrical safety on the water is not a suggestion. It is a life-saving requirement. I have spoken with marina developers whose projects were shut down because of incorrect wiring. The National Electrical Code (NEC) has specific, non-negotiable rules for docks.

The NEC code for docks1 is primarily covered in Article 555, "Marinas, Boatyards, and Commercial and Noncommercial Docking Facilities." This article mandates the use of ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs)2 for all outlets, specifies wiring methods (often requiring marine-grade cable), and details proper grounding and bonding to prevent stray current corrosion in the water.

Diving Deeper: Decoding NEC Article 555 for Safe Dock Construction

The NEC is a large document. Article 555 exists because water and electricity create unique and serious hazards. The goal is to prevent electrocution and fire.

The Core Principles of Dock Electrical Safety

The code focuses on three main areas: shock prevention3, fire prevention, and corrosion prevention.

-

Shock Prevention – The Role of GFCIs: This is the most critical rule. NEC 555.35 requires that all 125-volt, single-phase, 15- and 20-ampere receptacles on docks have GFCI protection. A GFCI monitors the current flow. If it detects even a small imbalance (as little as 4-6 milliamps, which could be flowing through a person in the water), it trips the circuit in a fraction of a second. This protection is required for every outlet, not just the first one in the circuit.

-

Wiring and Connection Methods: Ordinary indoor wiring will fail quickly in a marine environment.

- Wiring Types: The NEC specifies approved wiring methods, such as Type UF cable, or more commonly for professional installations, individual wires run in rigid metal conduit (RMC), intermediate metal conduit (IMC), or PVC conduit. The wires themselves are often THWN-2 or XHHW type, which are moisture-resistant.

- Marine-Grade Components: All junction boxes, fittings, and receptacles must be rated for "wet locations" or "corrosive environments." They are typically made of corrosion-resistant materials like stainless steel, brass, or high-quality plastics.

-

Grounding and Bonding – A Critical Distinction:

- Grounding (Equipment Grounding): This is the familiar green or bare wire that provides a safe path for fault current back to the source. It protects people from shock if a live wire touches a metal part of the dock.

- Bonding: This is equally important for docks. NEC 555.15 requires that all metal parts of the dock structure—including metal frames, railings, and even metal cables—be electrically bonded together and connected back to the equipment grounding conductor at the power source. This ensures all metal is at the same electrical potential. It prevents "stray current corrosion," which can rapidly eat away at aluminum or steel dock components, and it also reduces shock risk.

Key NEC Requirements Table

Here is a simplified guide to the major NEC rules for floating docks:

| NEC Section | Topic | Key Requirement | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| 555.35 | Receptacles | All 15A/20A, 125V receptacles must be GFCI-protected. | Prevents electrocution by cutting power if current leaks into the water. |

| 555.9 | Wiring Methods | Wiring must be suitable for wet locations. Supports listed cable types or conduit systems. | Prevents insulation failure, short circuits, and fires caused by moisture damage. |

| 555.15 | Bonding | All non-current-carrying metal parts must be bonded together and to the equipment grounding conductor. | Prevents stray current corrosion and ensures a safe path for fault current. |

| 555.11 | Overcurrent Protection | Overcurrent devices (breakers/fuses) must be readily accessible, often on shore. | Allows for quick shutdown in an emergency and protects circuits from overload. |

| 555.13 | Disconnect Means | A main disconnect must be provided on shore within sight of the dock. | Allows emergency personnel or dock staff to quickly kill all power to the dock. |

Important Note: The NEC is a model code adopted by states and local jurisdictions. You must always check with your local building department. They may have amendments or additional requirements beyond the base NEC. Hiring a licensed electrician familiar with marine codes is not just a good idea—it is often a legal requirement for obtaining a final inspection and permit. With the electrical rules in mind, we can move to the physical foundation: what makes the dock float.

How many barrels are needed for a floating dock?

A client called me in a panic. Their newly launched dock section was sitting too low in the water, almost submerged. They had guessed the number of floatation barrels. Guessing is the fastest way to sink your project, both literally and financially. Buoyancy is a precise science. You need to calculate it, not estimate it. Using the wrong number or type of floats is a fundamental engineering error.

The number of barrels (or floatation units) needed depends on the total dead load (weight of structure, decking, fixed equipment) and live load (people, furniture, boats). A basic calculation is: Total Buoyancy Needed1 = (Total Weight) x Safety Factor2 (often 1.5 to 2). Then, divide by the buoyancy rating of a single barrel. Always consult an engineer or the float manufacturer’s specifications.

Diving Deeper: The Engineering of Buoyancy and Floatation

This is not just about counting barrels. It is about understanding loads, distribution, and safety factors to ensure a stable, safe, and long-lasting platform.

The Step-by-Step Buoyancy Calculation

Let’s break down the process an engineer would use.

-

Calculate the Total Dead Load3 (DL): This is the weight of everything permanently attached.

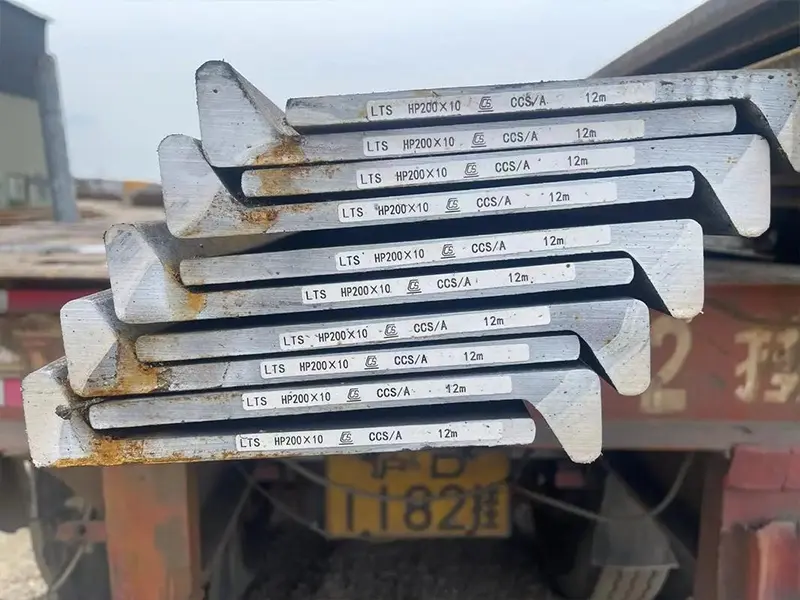

- Steel Frame: Weight of all marine angle steel, bulb flats, and plates. (We provide exact weight per meter for our sections).

- Decking Material: Weight of wood, composite, or aluminum decking.

- Fixed Equipment: Weight of cleats, light poles, electrical conduits, etc.

-

Calculate the Live Load4 (LL): This is the variable weight the dock must support.

- Occupancy Load: Code often specifies a minimum (e.g., 40-100 lbs per square foot). For a dock, consider the maximum number of people likely to be on a section.

- Dynamic Load: The weight of a boat resting on dock edges (finger piers), or people jumping.

-

Apply a Safety Factor2: Water conditions change. Floats can become waterlogged over time. You never design for the exact weight. A common safety factor is 1.5 to 2.0. This means your floatation system should provide 150% to 200% of the calculated total weight.

-

Select Floats and Determine Quantity: Floats are rated by their "displacement" or "buoyancy" in pounds or kilograms.

- Float Type5: Common options are sealed plastic barrels (HDPE), encapsulated foam blocks, or proprietary polyethylene floats.

- Buoyancy Rating6: A standard 55-gallon drum, if perfectly sealed, provides about 450-500 lbs of buoyancy. However, professional dock floats are designed for the purpose and have published ratings (e.g., 600 lbs, 1100 lbs).

- Number of Floats = Total Required Buoyancy / Buoyancy per Float. You always round up.

Critical Factors Beyond Simple Count

The placement of floats is as important as the number.

- Even Weight Distribution: Floats must be positioned under load-bearing points. Concentrating weight between floats will cause the dock to sag or "banana."

- Frame Stiffness: A rigid steel frame, using strong sections like bulb flat steel, helps distribute loads evenly across multiple floats.

- Freeboard7: This is the height of the dock deck above the waterline. You need enough freeboard to prevent waves from washing over the deck. A typical target is 12-18 inches. More buoyancy means more freeboard.

- Flotation Material Longevity8: Foam-filled floats can become waterlogged if damaged. Hollow plastic floats can fill with water if cracked. Choosing high-quality, UV-resistant floats from a reputable supplier is crucial.

Here is a simplified example table for a small dock section:

| Component | Estimated Weight | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Steel Frame (10’x10′) | 300 lbs | Based on marine angle steel sections. |

| Composite Decking | 200 lbs | |

| Electrical, Cleats | 50 lbs | |

| Total Dead Load3 (DL) | 550 lbs | |

| Live Load4 (4 people @ 200 lbs each) | 800 lbs | |

| Total Weight (DL+LL) | 1,350 lbs | |

| Safety Factor2 (x1.7) | x 1.7 | A mid-range factor. |

| Total Buoyancy Required | 2,295 lbs | 1,350 lbs * 1.7 = 2,295 lbs |

| Floats Selected | 4 units, each rated for 600 lbs | Common commercial float. |

| Total Buoyancy Provided | 2,400 lbs | 4 floats * 600 lbs = 2,400 lbs |

| Result | PASS | 2,400 lbs > 2,295 lbs required. |

This calculation shows the dock would float, but professional designs are more complex. Once you know your dock will float safely, you need to make sure the government agrees you can build it.

Do floating docks1 require permits?

You have the perfect design and the best steel. You start construction on the shoreline. Then, a local official shows up with a stop-work order. This happens all the time. Building in or near water is highly regulated. Permits are not bureaucracy. They are a process to protect public waterways, wildlife, and property rights. Skipping this step can lead to massive fines and being forced to remove your dock.

Yes, floating docks1 almost always require permits. The specific permits needed depend on location but commonly include a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) under Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act, a permit from the state environmental agency, and local building permits for electrical and structural work.

Diving Deeper: Navigating the Permitting Maze for Waterfront Construction

The permit process2 can be daunting. It involves multiple agencies at the federal, state, and local levels. Their primary concerns are environmental impact, navigation, and public safety3.

The Key Permitting Authorities and Their Focus

-

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE): This is often the most important permit for any work in "navigable waters of the United States."

- Jurisdiction: Covers nearly all lakes, rivers, streams, and coastal areas.

- Process: You typically apply for a "Nationwide Permit" (NWP) if your project is small and has minimal impact. Larger or more complex projects may need an "Individual Permit." The application requires detailed drawings showing the dock’s location, size, and materials.

- Their Concerns: Will the dock obstruct navigation? Will it impact wetlands or endangered species? Does it use environmentally sound materials (e.g., recommending non-creosote pilings)?

-

State Environmental/Natural Resources Agency: Each state has an agency (e.g., DNR, DEC) that protects water quality.

- Their Concerns: Will construction stir up sediments? Will the dock shade aquatic vegetation? Will boat usage or maintenance pollute the water? They often issue a "401 Water Quality Certification4," which is needed for the USACE permit.

-

Local Government (County/City):

- Building Department: Issues permits for the structural and electrical work, ensuring compliance with building codes (like the NEC we discussed) and zoning laws5 (setbacks from property lines).

- Planning/Zoning Department: Ensures the dock complies with local shoreline development rules.

-

Other Possible Agencies: In some areas, you may need approval from a local conservation district, a homeowners’ association (HOA), or a tribal government.

The Permit Process: Steps and Strategies

The process is not just filling out forms. It is a project phase.

| Step | Action | Tip / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-Application Research | Contact local building department6 and state agency. Determine all required permits. | Do this first. Rules vary wildly by location. |

| 2. Site Survey & Drawing Preparation | Hire a surveyor to map the shoreline and water depth. Create professional construction drawings. | Accurate drawings are crucial for approval. Include material specs (e.g., "marine-grade galvanized steel"). |

| 3. Application Submission | Submit applications, drawings, and fees to all relevant agencies, often simultaneously. | The USACE process can take 30-180 days. Start early. |

| 4. Agency Review & Public Notice | Agencies review for compliance. Larger projects may require a public comment period. | Be prepared to answer questions or modify your design. |

| 5. Permit Issuance & Conditions | If approved, you receive permits with specific conditions (e.g., seasonal work windows). | Read all conditions. You must build exactly as permitted. |

| 6. Inspections | Schedule required inspections during and after construction (electrical, final). | This is how the agency confirms you followed the plans. |

The Consequences of No Permit: If you build without a permit, you risk enforcement actions. This can include daily fines, a legal order to remove the dock at your own expense, and difficulties selling your property. The permit process2 exists for good reasons. Doing it right from the start saves time, money, and legal trouble. With the legalities understood, we can focus on the core physical question: what should you build it all out of?

What is the best material to build a dock?

"Best" is a tricky word. The best material for a private lake dock is different from the best for a commercial marina facing saltwater storms. I have supplied steel for docks in calm Thai resorts and heavy-duty ports in Saudi Arabia. The "best" material balances durability, maintenance, cost, and strength for your specific location and use. Choosing wrong means a future of constant repairs or a dangerous structure.

There is no single "best" material. The optimal choice depends on the environment and use. Pressure-treated wood is cost-effective for freshwater. Composite decking offers low maintenance. Aluminum is lightweight and corrosion-resistant. For the strongest, most durable structural frame, especially for large or commercial docks, galvanized or powder-coated marine-grade steel is often the best choice due to its superior strength and longevity.

Diving Deeper: A Side-by-Side Analysis of Dock Frame Materials

Let’s compare the most common options for the dock’s structural skeleton—the part that holds everything up. The decking surface1 is a separate choice.

Material Showdown: Wood, Aluminum, and Steel

Each material has clear strengths and trade-offs.

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure-Treated Wood (Frame)2 | Low initial cost. Easy to work with using basic tools. Familiar material. | Requires ongoing maintenance (staining, sealing). Can warp, crack, or rot over time, especially at connection points. Lower strength-to-weight ratio. Not ideal for large spans. | Small, private freshwater docks with limited budgets where owner accepts regular upkeep. |

| Aluminum (Frame)3 | Excellent corrosion resistance4 in salt and fresh water. Very lightweight, easy to handle and install. Low maintenance (no painting if marine alloy used). | Higher initial cost. Lower stiffness than steel, can feel "bouncy" on long spans unless heavily built. Requires specialized welding (MIG/TIG). Can suffer from galvanic corrosion if connected to dissimilar metals like steel. | Saltwater environments, residential docks where weight is a concern (e.g., portable sections), areas with low impact loads. |

| Marine-Grade Steel (Frame)5 | Superior strength and stiffness. Can create large, rigid spans with less material. High load-bearing capacity6 for commercial use. Long service life when properly galvanized and maintained. Can be fabricated into complex, robust shapes (using bulb flats, angles). | Heaviest material, requiring more buoyancy. Requires robust corrosion protection. Hot-dip galvanizing is essential. In saltwater, even galvanized steel needs eventual inspection and touch-up. Higher material and fabrication cost than wood. | Commercial marinas, large community docks, heavy-duty work platforms, docks in ice-prone areas, any application where maximum strength and durability are the top priorities. |

| Composite/Plastic Lumber7 | Often used for decking, not structure. Extremely low maintenance, no splinters, good slip resistance. | Not used for primary structure—lacks strength and stiffness. Can be expensive. Can warp or sag under load if not properly supported. | Decking surface on top of a steel or aluminum frame, combining low-maintenance walking surface with a strong skeleton. |

Why Steel Often Wins for Demanding Applications

For contractors building docks that must handle decades of abuse—like the ones our client Gulf Metal Solutions supplies in the Middle East—steel is the logical choice.

- Strength for Design Flexibility: Steel’s high strength allows for longer unsupported spans. This means fewer floats and a cleaner, more open design underneath. You can also easily weld on heavy cleats, ladder mounts, or lifting points without reinforcing the frame.

- Durability with Proper Protection: The key is the coating system. For marine steel docks, the process is critical:

- Material: Start with quality steel. Surface finish matters for coating adhesion.

- Fabrication: Cut, drill, and weld all components.

- Hot-Dip Galvanizing8: The entire fabricated frame is dipped in molten zinc. This creates a metallurgical bond that provides sacrificial protection. If the coating is scratched, the zinc corrodes first, protecting the steel.

- Topcoat (Optional): For extra longevity in harsh saltwater, a powder-coated or painted finish can be applied over the galvanizing.

- Repairability: A damaged steel section can be cut out and a new piece welded in place, then recoated. This is often harder with other materials.

The Hybrid Approach9: Many professional dock builders use a steel frame for ultimate strength and longevity, combined with composite or aluminum decking for a low-maintenance, attractive walking surface. This combines the best of both worlds: a tough skeleton and a user-friendly skin.

Conclusion

Building a successful floating dock requires more than just materials. It requires a respect for electrical safety codes, precise buoyancy engineering, thorough permitting, and selecting the right material—often marine-grade steel—for a frame that can last for decades on the water.

-

Discover the best options for decking surfaces to ensure safety and durability on your dock. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the pros and cons of Pressure-Treated Wood to understand its suitability for your dock project. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about the advantages of Aluminum in dock building, especially in saltwater environments. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understand the importance of corrosion resistance in choosing the right materials for your dock. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover why Marine-Grade Steel is favored for its strength and durability in demanding dock applications. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore how load-bearing capacity varies among dock materials to make an informed choice. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Find out how Composite/Plastic Lumber can enhance your dock’s decking with low maintenance and safety. ↩ ↩

-

Learn about Hot-Dip Galvanizing and its role in protecting steel docks from corrosion. ↩ ↩

-

Explore the Hybrid Approach to dock building, combining strength and low maintenance for optimal results. ↩