The strength of a modern ship against the immense power of the ocean doesn’t come from the outer plating alone. It comes from a hidden internal skeleton, where equal L-shaped steel plays a starring role. A weak or incorrect frame member can compromise the entire vessel.

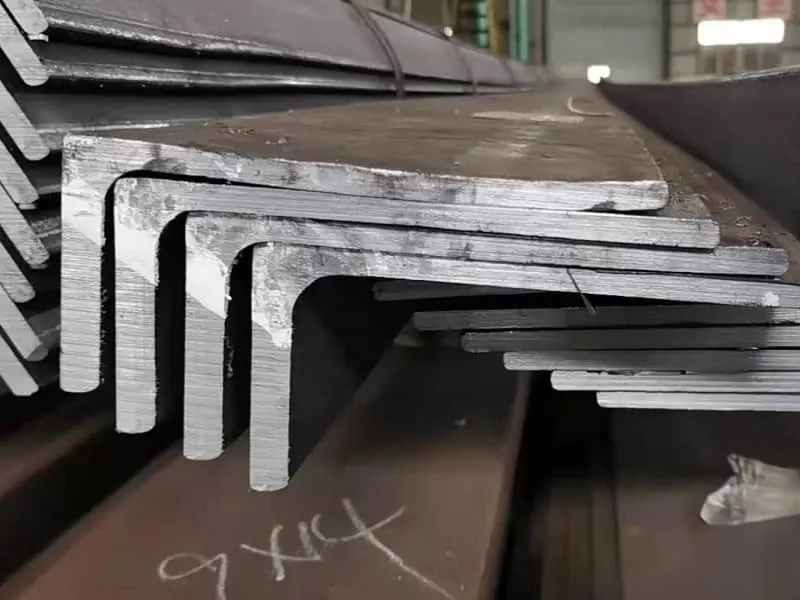

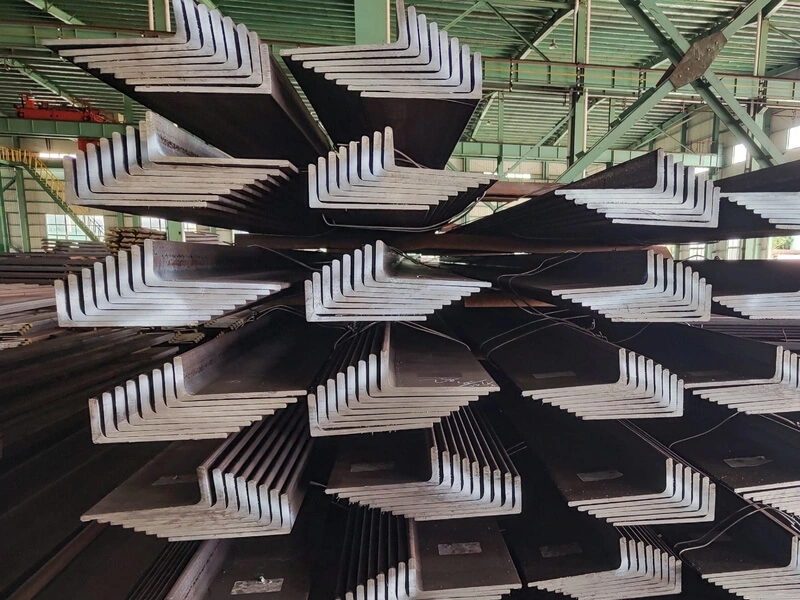

Equal L-shaped steel, or equal angle bar, is a primary material for reinforcing ship hulls. It is used as frames, longitudinals, and stiffeners, welded to the hull plating to create a rigid grid that resists bending, buckling, and torsional forces from waves and cargo loads. Selecting the correct marine-grade equal angle is critical for hull integrity and safety.

For shipbuilders, fabricators, and marine project managers, understanding this component is key to material procurement and construction quality. This guide will walk you through everything from the steel’s specifications to its precise role in the hull structure. Let’s start with the foundation: the type of steel used.

What kind of steel is used for ship hulls?

You cannot use the same steel for a ship’s hull as you would for a building frame. The marine environment demands unique properties. I’ve seen the consequences when a shipyard used substandard steel; the repair costs were astronomical. The hull is the ship’s first line of defense.

Ship hulls are built from marine-grade steel plates1 certified by classification societies like ABS, LR, DNV, or BV. These are not ordinary steels. They have controlled chemistry for weldability2 and must pass mandatory toughness (impact) tests at low temperatures. Common grades include ABS A, B, D, E and high-strength grades like AH32, AH36, DH36, and EH36. This ensures they withstand impact, fatigue, and cold water without brittle fracture.

The Rigorous Specifications of Marine Hull Steel

Marine steel is engineered for a specific, brutal purpose. It is a family of materials, each with a defined role based on its location in the ship.

Governance by Classification Societies

Every commercial vessel is built under the rules of a society like the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS)3. These societies approve the steel mills and the grades. The steel’s Mill Test Certificate (MTC)4 is your proof of this approval. It is a legal document that travels with the steel.

The Two Main Categories with a Purpose:

-

Ordinary Strength Hull Steel (Grades A, B, D, E):

- The letter indicates toughness level, not strength. Grade A is basic. Grade B is standard for most hull plating. Grade D and E offer progressively better impact resistance at lower temperatures (-20°C, -40°C). They are used in the forward part of the ship (the bow) where wave impact is highest and in ships operating in Arctic waters.

-

High Strength Hull Steel (Grades AH, DH, EH with numbers 32, 36, 40):

- The letter (A, D, E) still indicates the toughness level.

- The number indicates the minimum yield strength in kgf/mm². 36 means 355 MPa.

- Example: AH36 has 355 MPa yield strength with Grade A toughness. DH36 has the same 355 MPa strength but with the superior toughness of Grade D.

- Benefit: Using high-strength steel5 (AH/DH36) allows designers to use thinner plates and sections. This reduces the hull’s weight, which increases cargo capacity and improves fuel efficiency. This is vital for modern, economical ship design.

Critical Properties Beyond Strength:

- Toughness (Impact Resistance): Measured by a Charpy V-notch test6. A sample is cooled and struck. The energy absorbed (in Joules) must meet a minimum. This guarantees the steel will bend, not shatter, upon impact.

- Weldability: The entire hull is welded. The steel’s chemical composition, particularly the Carbon Equivalent (CE), is tightly controlled to prevent cracks during and after welding.

- Corrosion Resistance: While these steels will rust, their cleaner composition (lower sulfur/phosphorus) provides a better base for protective coatings and cathodic protection systems.

Grade Selection Table for Different Hull Zones:

| Hull Structure Location | Typical Steel Grade Used | Primary Reason for Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Midship Bottom & Side Shell | ABS Grade B or AH32 | Balances good toughness, strength, and cost for the largest part of the hull. |

| Sheer Strake (top edge of hull) & Keel | ABS Grade D7 or DH32/DH36 | Higher toughness to handle high stress concentrations and potential grounding impacts. |

| Fore Peak (bow area) | ABS Grade D7, E, or DH/EH36 | Maximum toughness to resist brittle fracture from slamming waves and cold temperatures. |

| Inner Bottom, Decks | ABS Grade A, B, or AH32/AH36 | Strength to support cargo; high-strength grades save weight. |

| Superstructure | Lower grades or AH32 for weight saving. | Less severe loading; reducing weight high up improves ship stability. |

When we supply steel to clients in Vietnam or Qatar, we don’t just ship "ship steel." We supply ABS AH36 plate or LR Grade D angles with full MTC traceability. This is the non-negotiable foundation. This certified steel is then formed into structures, which leads us to the next topic.

What is the introduction of steel structure?

Before diving into a ship’s hull, it helps to understand basic steel structure principles. A ship’s hull is essentially a massive, floating, watertight steel structure. The same engineering concepts that make a bridge strong also apply to a ship. A fabricator in Romania once struggled because they didn’t see the hull as an integrated structure.

A steel structure is a load-bearing framework made of connected steel members (beams, columns, plates). Its design focuses on transferring loads (weight, wind, waves) safely to the foundation through tension, compression, and bending resistance. Key concepts include strength, stiffness, stability, and connection design, all of which are paramount in ship hull construction. The hull is a complex box girder designed to float and carry dynamic loads.

Core Principles of Structural Engineering Applied to Ships

Understanding a few fundamental ideas will help you see why equal L angles are so useful and how a hull works.

1. Load Path and Force Transfer

Every structure must have a clear path for forces to travel. In a ship:

- Cargo Weight -> Deck -> Deck Beams -> Frames -> Hull Plating -> Water.

- Wave Impact -> Hull Plating -> Frames & Longitudinals -> Main Hull Girder.

The structure collects分散的 loads and channels them into major members.

2. Member Functions: Tension, Compression, Bending

- Tension Members: Pulled apart. (Example: Chains, some hull braces).

- Compression Members: Pushed together. Prone to buckling. (Example: Columns, hull frames under deck load).

- Bending Members: Subject to both tension and compression. (Example: Beams, the entire hull girder bending between waves).

- Shear: Forces trying to slide layers past each other. (Example: Welds, web of a beam).

3. The Role of Stiffeners and Bracing

Large, thin plates (like hull plating) are weak against buckling. They need support.

- Stiffeners: Smaller members (like L angles) attached perpendicular to a plate. They divide the large plate into smaller, stronger panels, dramatically increasing its resistance to bending and buckling under pressure.

- Bracing: Diagonal members in a frame that create triangles. Triangles are geometrically stable shapes that prevent the frame from racking (deforming into a parallelogram) under sideways forces.

4. Connections: The Critical Link

The strength of a structure is only as good as its connections. In shipbuilding, this means welding. The weld must be as strong as the members it joins. The steel’s weldability (from its controlled chemistry) is therefore essential.

How This Applies to Equal L Angles in a Hull:

An equal L angle is a simple but efficient structural member.

- As a Stiffener: Its L shape provides high stiffness in two directions when welded along one leg to a plate. It acts as a small beam, supporting the plate.

- As a Frame: Multiple angles can be connected to form a larger frame member that runs around the ship’s cross-section, transferring loads from the deck and bottom.

- As Bracing: Used diagonally within internal structures for stability.

Structural Element Comparison:

| Structural Element | Analogy in a Building | Analogy in a Ship Hull |

|---|---|---|

| Columns / Vertical Load-bearing walls | Support floors and roof. | Frames (often made from angles) support decks and transfer load to the hull. |

| Beams / Joists | Span between columns, support floors. | Deck beams, longitudinals (often angles or bulb flats) support deck plating. |

| Bracing | Diagonal elements in a steel frame for wind resistance. | Diagonal braces inside the hull and superstructure for hull rigidity. |

| Shear Walls / Diaphragms | Resist lateral forces (wind, earthquake). | The entire hull plating, stiffened by angles, acts as a massive shear web. |

With this structural mindset, you can better appreciate the specific, complex arrangement of these members in a ship’s hull, which is our next focus.

What is the hull structure1 of a ship?

The hull is not a simple shell. It is a highly engineered, layered structure designed to be both strong and watertight. Think of it as a long, hollow box girder that must also float and move. A misunderstanding of this structure led a new shipyard in Thailand to under-specify their angle steel, resulting in a hull that was not stiff enough.

A ship’s hull structure1 is a complex framework primarily made of longitudinal and transverse members2 attached to the outer shell plating. Key components include the keel3 (backbone), frames (transverse ribs), longitudinals (longitudinal ribs), stringers, and bulkheads4. Equal L-shaped steel is extensively used for frames, stiffeners5, and brackets within this system to provide rigidity and distribute loads. This grid system withstands global bending, local water pressure, and torsional stresses.

The Anatomy of a Modern Hull: A Detailed Breakdown

Most large commercial ships use a longitudinal framing system for the bottom and sides, combined with transverse framing for large spaces. Let’s explore the main parts.

1. The Foundation: Keel and Bottom Structure

- Keel: The central backbone running from bow to stern. It is the first part laid during construction and takes major stresses.

- Bottom Plating: The steel plates forming the ship’s bottom.

- Bottom Longitudinals: Long, fore-and-aft members (often bulb flats, sometimes large angles) welded to the bottom plating. They stiffen it against water pressure and global bending.

- Floors: Transverse members in the double bottom that connect the sides and support the longitudinals.

2. The Sides: Shell Plating and Side Framing

- Side Shell Plating: The curved steel plates forming the ship’s sides.

- Side Frames: These are the transverse ribs of the ship. They are often made from equal L angles6 or built-up sections. They run vertically up the sides, providing the ship’s transverse shape and strength.

- Side Longitudinals: Fore-and-aft members on the side shell, similar to the bottom. They work with the frames to stiffen the plating.

3. Internal Strengthening: Decks, Bulkheads, and Girders

- Decks: Horizontal "floors" of the ship. Their plating is stiffened by deck beams7 (transverse) and deck longitudinals (fore-and-aft), often made of angles or bulb flats.

- Bulkheads: Vertical walls inside the hull that divide it into compartments (for watertight integrity and strength). They are plated structures stiffened by a grid of vertical and horizontal stiffeners5, very commonly made from equal L angles6.

- Stringers and Girders: Large, heavy members that run longitudinally along the sides and centerline, collecting loads from frames and beams.

The Role of Equal L Angles in This System:

Equal L angles are the workhorse for many secondary structural members due to their availability, ease of welding, and good strength.

- Frames: L angles of specific sizes form the ship’s transverse ribs.

- Stiffeners: On bulkheads4 and non-critical plating, L angles are welded as stiffeners5.

- Brackets: Small triangles cut from L angles are used everywhere to reinforce connections between members.

Hull Structure Component Guide:

| Component | Primary Function | Common Profile Used | Why It Works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side/Ring Frames | Provide transverse shape and strength, support decks. | Equal L Angle (e.g., L200x200x16) | The L shape provides strength in two directions, is easy to fit to the curved hull, and is simple to weld. |

| Bulkhead Stiffeners | Prevent buckling of bulkhead plates under water pressure. | Equal L Angle (e.g., L150x150x12) | Lightweight, easy to install in a grid pattern, provides effective stiffness. |

| Deck Beams | Support deck plating between transverse frames. | Equal L Angle or Bulb Flat | Angles are cost-effective for lighter loads; bulb flats offer higher efficiency for heavy cargo areas. |

| Brackets (Knees) | Reinforce connections (e.g., between frame and deck beam). | Triangular pieces cut from L Angle | Utilizes material efficiently; the angle leg provides a ready surface for welding. |

For a shipbuilder or a supplier like us, knowing this structure is key. It tells us that a client ordering "ABS Grade B L200x200x16" likely needs it for main hull frames8. This specificity allows us to provide the right material from the right mill. Now, the final question is: what is the absolute best steel for this demanding application?

What is the best steel for ship building?

There is no single "best" steel for all ships. The best choice is the steel that most precisely and cost-effectively meets the specific requirements of the vessel’s design, route, and regulatory rules. Recommending one grade for everything is like recommending one vehicle for all jobs—it’s not practical.

For primary hull structures, the best steels are those certified by classification societies1 (ABS, LR, DNV). For most ocean-going vessels, grades like ABS Grade B2, D, AH32, and AH36 offer the optimal balance of strength, toughness, weldability3, and cost. The "best" is defined by the specific application: AH36/DH36 for high-strength weight savings, Grade D4/E for cold environment toughness, and Grade A/B for cost-effective secondary structures. It is always a performance-to-cost optimization.

Selecting the Optimal Steel: A Decision Framework

The choice involves balancing multiple, sometimes competing, factors: strength, toughness, cost, availability, and fabrication requirements.

1. The Hierarchy of Needs

- Safety & Compliance (Non-Negotiable): The steel must meet the rules of the chosen classification society. This is the first filter.

- Performance: It must have the yield strength and toughness required by the structural calculations for each part of the ship.

- Fabricability: It must be weldable and formable using the shipyard’s standard processes.

- Economic Efficiency: It should provide the required performance at the lowest total cost (material + fabrication + lifecycle).

2. Application-Specific "Best" Choices

- Large Container Ship/Bulk Carrier Midship Hull:

- Challenge: Need high strength to reduce plate thickness, saving weight to carry more cargo.

- Best Steel: AH36 or AH40 high-strength steel5. The weight saving translates directly into increased revenue.

- Ice-Class Vessel or Offshore Supply Vessel:

- Challenge: Operating in freezing temperatures with ice impact.

- Best Steel: Grade D4, E, DH36, or EH36. The enhanced low-temperature toughness6 is critical to prevent brittle fracture.

- General Cargo Ship or Tanker on Standard Routes:

- Challenge: Balanced requirements for strength, toughness, and cost.

- Best Steel: ABS Grade B2 or AH32. Provides excellent all-around performance at a competitive price point.

- Ship’s Superstructure and Interior:

- Challenge: Non-critical structures where weight saving high up improves stability.

- Best Steel: Grade A or lower-strength grades. Cost-effectiveness is the priority here.

3. The Role of Equal L Angles in this Selection

The "best steel" principle applies fully to angle sections. An angle used as a main frame in the bow will likely need to be Grade D4 or DH36. The same size angle used for a non-watertight partition inside the accommodation block can be Grade A.

Comparison of Steel Grades for Hull Angles:

| Intended Use for the Equal L Angle | Recommended Grade | Rationale | Cost Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main hull frames in forward 1/4 length of ship. | ABS Grade D4 or DH36 | Mandatory for impact and low-temperature toughness6 in this high-stress zone. | Premium price for enhanced toughness testing and chemistry control. |

| Main hull frames in midship area. | ABS Grade B2 or AH32/AH36 | Standard toughness is sufficient. High-strength grades reduce weight. | Grade B is standard cost. AH grades command a moderate premium for strength. |

| Bulkhead stiffeners in cargo holds. | ABS Grade A or B | Subject to moderate pressure. Grade A is often sufficient, Grade B adds a safety margin. | Grade A is the most economical certified marine grade. |

| Non-structural interior brackets and supports. | Mild Steel (e.g., A36) | No marine certification required. | Lowest cost. Must be properly coated for corrosion control. |

For our clients—rational, results-driven businesses—the answer is clear. The "best" steel is the one that comes with reliable certification (MTC), consistent quality, and is supplied by a partner who understands these distinctions and can deliver the right grade at a competitive price. This ensures their project, whether a tanker for Saudi Arabia or a bulk carrier for the Philippines, is built on a foundation of safety and value.

Conclusion

Equal L-shaped steel is a fundamental component in ship hull reinforcement, serving as frames and stiffeners. Its effectiveness hinges on selecting the correct marine-grade steel (like ABS B, D, or AH36) based on the hull’s structural requirements, ensuring a vessel that is strong, safe, and efficient.

-

Understanding classification societies helps ensure compliance and safety in shipbuilding. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the applications of ABS Grade B steel to see its benefits in various ship designs. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the factors influencing weldability to ensure successful fabrication in shipbuilding. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understanding Grade D properties can help in selecting the right materials for specific ship structures. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn how high-strength steel can enhance ship performance and reduce weight. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover the significance of low-temperature toughness in ensuring ship safety in icy conditions. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Deck beams support the ship’s structure; learn about their design and importance. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Hull frames are key to a ship’s shape and strength; understanding them is essential for builders. ↩