You are designing a ship’s hull stiffener. You need to select the right bulb flat size to handle the immense pressure of the sea. A wrong calculation can lead to excessive deflection or even structural failure. The key to this decision is a single number: the section modulus.

To calculate the section modulus (Z) for bulb flat steel, you need its precise cross-sectional dimensions (web height, flange width, bulb radius). The formula is Z = I / y, where I is the moment of inertia of the section about its neutral axis, and y is the distance from the neutral axis to the outermost fiber. For standard bulb flats, use pre-calculated tables from classification society rules (like DNV, ABS) or manufacturer data. For custom sizes, perform the calculation by dividing the complex shape into simple rectangles, calculating I for each, and applying the parallel axis theorem.

You now know the goal and the basic formula. But to apply this confidently to bulb flats and other sections, you must build from the ground up. What is section modulus fundamentally? How do you find it for common beams? What if the shape is not simple? Let’s answer these questions step by step.

How to calculate section modulus of steel?

You see the symbol "Z" or "S" on engineering drawings. It looks like abstract math, but it is a direct measure of a steel section’s bending strength. Not knowing how to find it leaves you guessing about your design’s safety.

You calculate the section modulus (Z) of a steel section by dividing its moment of inertia (I) by the distance (c) from its neutral axis to the outermost fiber: Z = I / c. For simple symmetric shapes (like rectangles, I-beams), use standard formulas. For complex shapes like bulb flats, break the shape into simple parts, calculate the moment of inertia for each part about the section’s overall neutral axis, sum them to get total I, then divide by the maximum distance to the edge.

The calculation is a process: find the geometry’s center, find its resistance to bending (I), then normalize that resistance to the farthest point (Z). Let’s break down this process.

The Three-Step Calculation Framework

Follow these steps for any cross-section.

- Locate the Neutral Axis (Centroid): This is the axis about which the section bends. For symmetric shapes, it’s the centerline.

- Calculate the Moment of Inertia (I): This measures the distribution of material relative to the neutral axis. More material farther away gives a higher I.

- Compute the Section Modulus (Z): This takes I and scales it by the maximum distance to the edge, giving a number directly used in bending stress formulas.

Applying the Steps to Common Shapes

This table shows how to execute these steps for basic shapes, forming the foundation for complex shapes like bulb flats.

| Step | Example: Rectangle (Width=b, Height=h) | Example: I-Beam (Flange bf, Web hw, tf, tw) | Key Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Find Neutral Axis (NA) | For a rectangle bending about its strong axis (horizontal NA), the NA is at h/2 from the bottom. | The NA is at the centroid. For doubly symmetric I-beams, it is at the vertical center. Calculate using: ȳ = Σ(Ai * yi) / ΣAi for composite shapes. | The neutral axis is where bending stress is zero. |

| 2. Calculate Moment of Inertia (I) | Formula: Ixx = (b * h³) / 12. This is about the centroidal axis. | Break into 3 rectangles: top flange, web, bottom flange. Calculate I for each about its own centroid, then use the Parallel Axis Theorem: I_total = Σ(Ii + Ai * di²), where di is the distance from part’s centroid to the section’s NA. | I measures how "spread out" the material is. The Parallel Axis Theorem is crucial for composite shapes. |

| 3. Compute Section Modulus (Z) | Z = I / c. Here, c = h/2. So, Z = (b h³ / 12) / (h/2) = (b h²) / 6. | Z = I / c, where c is the distance from the NA to the extreme top or bottom fiber (usually h/2 for symmetric beams). | Z is the direct link to bending stress: σ = M / Z, where M is the bending moment. A higher Z means lower stress for the same bending moment. |

For standard structural shapes like wide-flange beams, you never do this calculation by hand. You look up the value in a steel manual. The same principle applies to bulb flats in shipbuilding. Naval architects use pre-calculated tables from classification society rules where Z is listed for every standard bulb flat size (e.g., HP 100×6, HP 120×7). The "how to calculate" knowledge is essential for understanding what those tables mean and for verifying or designing non-standard sections.

What is the section modulus of a steel beam?

You select a beam from a catalog. Next to the weight, you see "Zx" and "Zy." These are not random codes. They are the beam’s passport for carrying load. Choosing a beam with insufficient section modulus is an engineering error.

The section modulus (Z) of a steel beam is a geometric property that predicts its elastic bending strength. It is a single number, in units of length cubed (cm³ or in³), that relates the applied bending moment (M) to the maximum bending stress (σ) in the beam via the formula: σ = M / Z. A beam with a larger section modulus will have lower stress under the same load, meaning it is stronger in bending. For I-beams, Zx refers to bending about the strong (x-x) axis, and Zy refers to the weak (y-y) axis.

Think of Z as the beam’s bending efficiency rating. It condenses the complex geometry of the cross-section into one useful number for stress calculation.

Section Modulus as a Design Tool

In practical design, engineers use Z in three main ways.

- Sizing Beams: Given a known maximum bending moment (M) and allowable stress (σ_allow), you calculate the required section modulus: Z_required = M / σ_allow. Then you select a beam from a table with a Z value greater than or equal to Z_required.

- Checking Stress: For an existing beam under a known load, you calculate the actual stress: σ_actual = M / Z. You check that σ_actual ≤ σ_allow.

- Comparing Sections: You can directly compare the bending strength of two different beam sizes or types by comparing their Z values.

Understanding Zx and Zy for Common Beams

This table explains the dual values for asymmetric bending resistance.

| Section Modulus | Axis it Applies To | What it Measures | Typical Value Example (W8x31 Beam) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zx (Major Axis Modulus) | Bending about the strong, horizontal x-x axis (causing the beam to bend like a smile/frown). | Primary bending strength. This is the value used 95% of the time for beams supporting loads on their top flange. | For a W8x31 beam, Zx ≈ 30.4 in³. This is its main rating for carrying floor or deck loads. |

| Zy (Minor Axis Modulus) | Bending about the weak, vertical y-y axis (causing the beam to bend sideways). | Lateral-torsional buckling resistance. Important when the beam is not fully braced against sideways movement or for specific loading conditions. | For the same W8x31 beam, Zy ≈ 4.47 in³. It is much smaller, showing the beam is weak in sideways bending. |

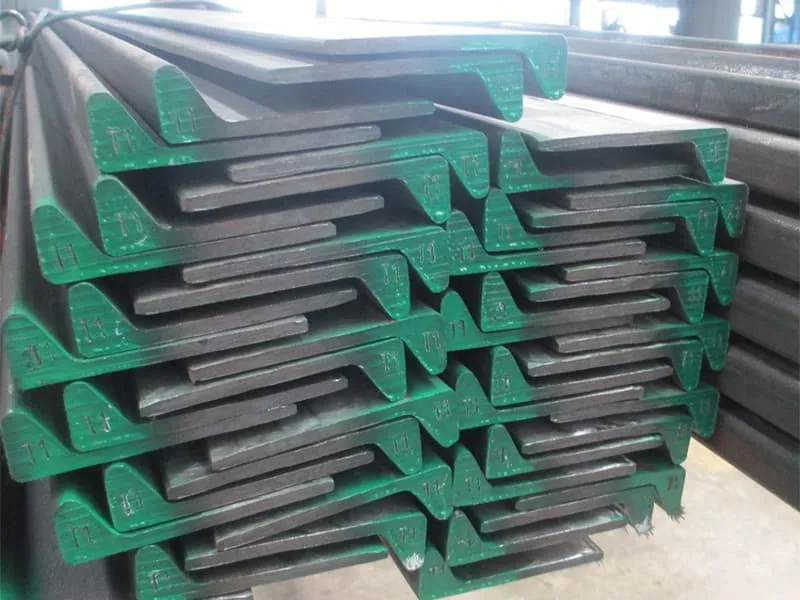

| Application in Shipbuilding | For a bulb flat used as a longitudinal stiffener on a ship’s hull, the relevant section modulus is analogous to Zx. The bulb flat bends about the axis parallel to the attached plate. | The bulb adds material away from the neutral axis (the plate), significantly increasing the Z value compared to a simple flat bar. This makes it highly efficient. | A HP 120×7 bulb flat has a much higher section modulus than a 120mm x 7mm flat bar of the same weight, due to the bulb’s geometry. |

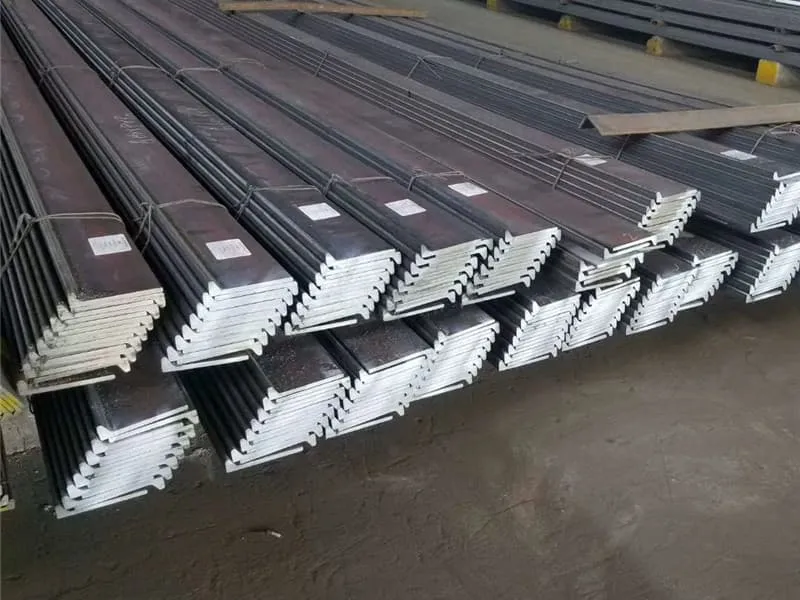

This is why bulb flats are the standard in shipbuilding. For the same weight of steel, the bulb flat provides a significantly higher section modulus (Z) than a simple flat bar. This means the hull can be stiffened more effectively, reducing plate thickness and overall weight while maintaining strength—a critical factor for vessel efficiency. When we supply Bulb Flat Steel to shipyards in Vietnam or Romania, they are not just buying a shape; they are buying a specific, pre-calculated bending performance defined by its section modulus in the classification society rules.

How to calculate section modulus of irregular shape?

You have a custom bracket or a complex built-up section like a bulb flat. There is no pre-calculated table. This is where engineering fundamentals take over. The process is systematic, not magical.

To calculate the section modulus of an irregular shape, use the composite area method: 1) Divide the shape into simple rectangles. 2) Find the centroid (neutral axis) of the entire shape. 3) Calculate the moment of inertia (I) of each rectangle about its own centroid. 4) Use the Parallel Axis Theorem to shift each I to the overall neutral axis and sum them. 5) Find the distance (c) from the neutral axis to the farthest point. 6) The section modulus is Z = I_total / c.

This method transforms complexity into a series of simple, manageable steps. The core tool is the Parallel Axis Theorem, which accounts for the position of each part.

The Composite Area Method: A Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Let’s apply this to a simplified bulb flat profile to see it in action.

- Division: Break the bulb flat into simple parts: the flange (a thin rectangle), the web (a tall rectangle), and the bulb (approximated as a rectangle or a circle segment).

- Centroid Calculation: Create a table to find the vertical location (ȳ) of the entire section’s neutral axis.

- Moment of Inertia Summation: Calculate and transfer each part’s I to the overall NA.

- Final Calculation: Divide the total I by the extreme fiber distance.

Example: Simplified Bulb Flat Calculation

Assume a bulb flat with a 100mm web, 7mm thick, a 12mm flange, and a bulb approximated as a 20mm x 10mm rectangle.

| Step | Action for Part 1 (Web) | Action for Part 2 (Flange) | Action for Part 3 (Bulb) | General Formula/Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dimensions & Area | h=100mm, t=7mm. A1 = 100*7 = 700 mm². | w=12mm, t=7mm. A2 = 12*7 = 84 mm². | Approx. as 20x10mm rect. A3 = 200 mm². | Ai = area of part i. |

| 2. Locate Part Centroid (from bottom) | y1 = h/2 + flange_thk + bulb_ht = 50+7+10=67mm. | y2 = flange_thk/2 + bulb_ht = 3.5+10=13.5mm. | y3 = bulb_ht/2 = 5mm. | Measure from a common reference line (e.g., bottom of bulb). |

| 3. Find Overall Neutral Axis (ȳ) | ȳ = (Σ(Ai yi)) / ΣAi = (A1y1 + A2y2 + A3y3) / (A1+A2+A3). Calculate to find ȳ. | This is the weighted average position of all areas. | ||

| 4. Distance from Part Centroid to NA (d) | d1 = y1 – ȳ. | d2 = y2 – ȳ. | d3 = y3 – ȳ. | di = distance to shift inertia. |

| 5. Part’s Own I about its centroid (I_ci) | I_c1 = (t h³)/12 = (7100³)/12. | I_c2 = (w t³)/12 = (127³)/12. | I_c3 = (20*10³)/12. | I_ci for rectangle = (base*height³)/12. |

| 6. Apply Parallel Axis Theorem | I1 = I_c1 + A1*(d1²). | I2 = I_c2 + A2*(d2²). | I3 = I_c3 + A3*(d3²). | I_total = I1 + I2 + I3. |

| 7. Find Extreme Fiber Distance (c) | c_max = distance from ȳ to farthest point (top of web or bottom of bulb). | Use the larger of (ȳ) and (total height – ȳ). | ||

| 8. Calculate Section Modulus (Z) | Z = I_total / c_max. | Result is in mm³. For engineering, convert to cm³ (divide by 1000). |

This process, while detailed, is exactly how the values in classification society tables are derived (using more precise bulb geometry). For a shipyard engineer designing a custom built-up section, this skill is essential. For a buyer or project manager, understanding this process highlights the engineering rigor behind a simple-looking product like bulb flat steel. It underscores why precise dimensional tolerances matter—a few millimeters off in the bulb size can change the calculated Z, affecting the design’s safety factor.

How to calculate zx for steel?

On a beam table, you see "Zx1." In a stress formula, you use "Z." Are they the same? How do you get the specific number for your beam? This is the final step in applying the theory.

To calculate Zx1 for a given steel section, you need its moment of inertia2 about the x-axis (Ix) and the distance from the x-axis to the extreme fiber in the x-direction (cx). The formula is Zx1 = Ix / cx. For standard rolled sections3 like I-beams, channels, or bulb flat4s, you do not calculate it; you look up the pre-calculated value in the manufacturer’s catalog or the relevant structural steel handbook (e.g., AISC Manual5 in the US, European profile tables).

Zx is simply the section modulus for bending about the specific x-axis. The "x" denotes the axis. The calculation method depends entirely on whether you have a standard or non-standard section.

Sources of Zx Values: From Tables to Calculations

There are three main paths to finding Zx, depending on your situation.

- Using Standard Tables: This is the fastest and most accurate method for common, mass-produced sections.

- Engineering Software: Programs like AutoCAD, SolidWorks, or dedicated structural software can calculate Zx1 instantly for any drawn profile.

- Manual Calculation: This is the method of last resort for truly custom shapes, using the composite area method6 described earlier.

A Practical Guide to Finding Zx1

This table helps you choose the right method and know where to look.

| Scenario | Recommended Method to Find Zx1 | Step-by-Step Action | Notes & Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| You have a standard I-beam, Channel, or Angle | Look up in published tables. | 1. Identify the section designation (e.g., W12x26, C8x11.5, L4x4x1/2). 2. Open the AISC Steel Construction Manual (or equivalent European/Asian standard table). 3. Find the section in the index. 4. Read the value for "Sx" or "Zx1" from the table. |

"Sx" is the elastic section modulus7. "Zx1" is the plastic section modulus7. For elastic design (most common), use Sx. Ensure you use the correct axis (x-x vs. y-y). |

| You have a standard shipbuilding bulb flat4 | Look up in classification society rules. | 1. Identify the bulb flat4 code (e.g., HP 120×7, HP 100×6). 2. Refer to the shipbuilding rules from DNV, ABS, or LR. 3. Find the section on hull construction/scantlings. 4. Use the provided section modulus7 value (often called "Z" or "SM") for that profile. |

These values are authoritative for marine design. They are derived from precise geometry and are non-negotiable for class approval. |

| You have a custom or built-up section | Use CAD software or manual calculation. | 1. Draw the precise cross-section in CAD software. 2. Use the software’s "Mass Properties" or "Section Properties" tool. 3. The software will output Ix, Iy, and the corresponding Sx, Sy values. |

This is efficient and accurate. It eliminates human error in the composite area calculation. It is the modern standard for custom work. |

| You need to verify or understand a value | Perform a manual approximate calculation. | Follow the composite area method6. Use it as a sanity check against table or software values. If there’s a large discrepancy, check your dimensions or the source data. | This builds deep understanding but is time-consuming. It is excellent for learning or troubleshooting. |

For buyers and project managers, you typically don’t calculate Zx1. Your role is to ensure the supplied product matches the specified profile that has the required Zx1. When Gulf Metal Solutions orders Bulb Flat Steel for a barge project, the ship design specifies "HP 100×6" because the naval architect’s calculations require the specific Zx1 value of that profile. Our job as the supplier is to deliver bulb flat4s that match the dimensional standard (height, flange width, bulb geometry) so that the as-built Zx1 is guaranteed. This is another layer of "quality consistency"—dimensional accuracy directly translates to guaranteed structural performance.

Conclusion

Calculating the section modulus, especially for efficient shapes like bulb flats, is fundamental to safe marine design. Use standard tables for common sections, apply the composite area method for irregular shapes, and always verify that supplied materials match the specified dimensions to ensure the calculated strength is achieved in reality.

-

Understanding Zx is crucial for structural design, as it relates to the strength and stability of beams. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

The moment of inertia is a key factor in beam design, influencing load capacity and deflection. ↩

-

Standard rolled sections are essential for efficient design and construction in structural engineering. ↩

-

Bulb flats are critical in shipbuilding for enhancing structural integrity and reducing weight. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

The AISC Manual is a comprehensive resource for engineers, providing essential data for steel design. ↩

-

The composite area method is a fundamental technique for calculating properties of complex shapes. ↩ ↩

-

Section modulus is vital for assessing the strength of structural elements under bending. ↩ ↩ ↩