Your ship’s structural bracket bends under load. The material grade is correct, but the size is wrong. You chose an L-angle based on experience, not calculation. This mistake costs you time, money, and safety.

Calculate the section modulus for L-shaped steel by determining its cross-sectional area, locating the centroid (neutral axis), and then calculating the second moment of area (I) about that axis. The section modulus (Z) is then I divided by the distance to the outermost fiber (y_max): Z = I / y_max.

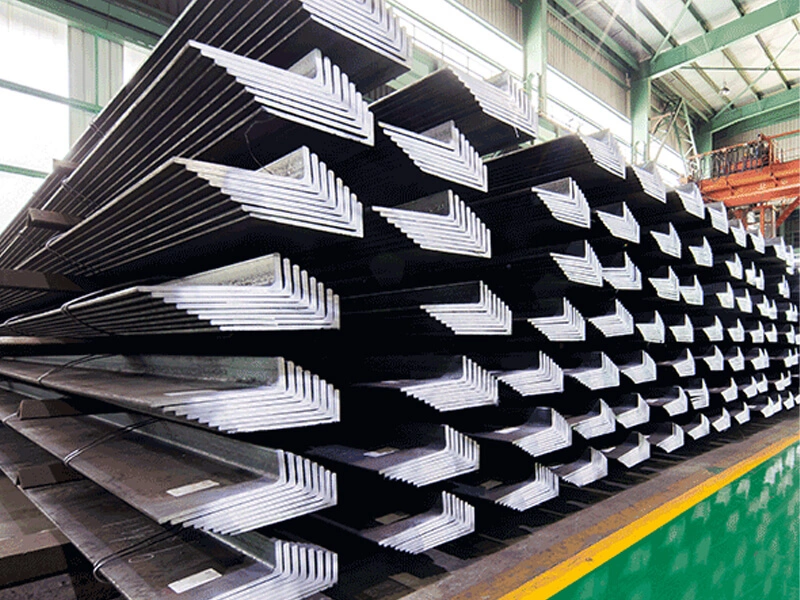

As a supplier, I often get questions from fabricators in Saudi Arabia or Vietnam. They want to verify a design or choose the right size angle. You do not need to be a naval architect to grasp the basics. Understanding section modulus helps you communicate better with engineers and make smarter purchasing decisions. Let’s break down this concept from the general principle to its specific marine application.

How to calculate section modulus of steel?

A fabricator receives a drawing specifying an L150x100x12 angle. He needs to check if it is strong enough for a new bracket design. Guessing could lead to failure. A basic calculation gives him certainty and saves the project.

To calculate the section modulus of any steel shape, you first find its centroid. Then you calculate the Second Moment of Area (I) about the neutral axis through this centroid. Finally, divide I by the maximum distance from the neutral axis to the outer edge of the section (y_max or c).

The term "section modulus" (Z) sounds complex. But it is just a single number that tells you how strong a beam or bracket is in bending. A higher Z means a stronger section. The calculation process is systematic. We can look at it step by step for a standard shape like an L-angle.

A Step-by-Step Guide to Calculating Section Modulus (Z)

| Step | Action | Explanation & Purpose | Practical Note for L-Angles |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Define the Geometry | Note all dimensions. For an equal L-angle: leg length (b) and thickness (t). For unequal: lengths (b1, b2) and thickness (t). | You cannot calculate anything without precise dimensions. These come from standard tables or the supplier’s specification. | We provide exact dimensional tolerances with our marine L-shaped steel. This ensures your calculations are based on real, deliverable sizes. |

| 2. Find the Centroid (C.G.) | The centroid is the "balance point" of the cross-sectional area. For simple shapes, formulas exist. For L-angles, it is not at the geometric corner. | The neutral axis (the line of zero stress during bending) passes through the centroid. All bending calculations refer to this axis. | For an unequal L-angle (b1 x b2 x t), the centroid distances (x̄, ȳ) from the outer edges are: x̄ = (b2t(b2/2) + (b1-t)t(t/2)) / Area ȳ = (b1t(b1/2) + (b2-t)t(t/2)) / Area |

| 3. Calculate the Second Moment of Area (I) | This measures the distribution of area around the neutral axis. Use the parallel axis theorem: I = I_centroid + A*d². | It quantifies the shape’s resistance to bending. More material farther from the centroid gives a much higher I. | You calculate I_x about the horizontal neutral axis and I_y about the vertical one. For bending in different directions, you need the appropriate I. |

| 4. Determine y_max | Find the longest perpendicular distance from the neutral axis to the farthest point on the cross-section. | This is the point of maximum stress. The section modulus uses this to convert I into a direct measure of bending strength. | For an L-angle, you typically have two different y_max values, one for each leg. This gives you two different Z values (Z_x and Z_y). |

| 5. Compute Section Modulus (Z) | Z = I / y_max | This is the final result. The allowable bending moment (M) the section can resist is: M = σ * Z, where σ is the allowable stress of the steel. | You use the smaller Z value for the bending direction you are checking, as it represents the weaker axis. |

In practice, naval architects and engineers use software or pre-calculated tables from steel handbooks. However, understanding this process is powerful. It allows a project manager or fabricator to double-check designs or understand why a specific size was specified. For example, when our client Gulf Metal Solutions inquires about L-shaped steel, they sometimes ask for the standard dimensions and weights. This data is the starting point for their engineers’ calculations. Our ability to provide consistent, certified material with guaranteed dimensions makes their design verification process reliable.

What is the hull section modulus?

A shipowner wants to increase the cargo load on his bulk carrier. The naval architect says the hull section modulus is the limiting factor. This is not a vague concept; it is a precise calculation that determines the ship’s backbone strength and legal loading capacity.

The hull section modulus is a key structural metric for the entire ship’s cross-section. It represents the bending strength of the ship’s hull girder at its midship region. Classification societies set minimum required values to ensure the hull can withstand global bending forces from waves and cargo.

Think of the entire ship hull as a giant, hollow beam floating on the water. As waves pass, the hull "hoggs" (arches upward) or "sags" (bends downward). The hull section modulus (often denoted as Z_ship or Z_required) measures this giant beam’s resistance to such bending. It is calculated for the entire midship section, not just one piece of steel.

Understanding the Hull Section Modulus and Its Components

| Concept | Description | Relation to Individual Components (like L-Angles) |

|---|---|---|

| The Ship as a Beam | The hull is treated as a single, complex beam. The neutral axis runs through its centroid. All longitudinal strength members (keel, bottom plating, deck plating, side shell, longitudinal stiffeners) contribute to its strength. | Every piece of steel that runs longitudinally (fore-and-aft) is part of this "beam." This includes long L-angles used as longitudinal stiffeners on bulkheads or decks. |

| Calculation Principle | The hull section modulus (Z) is calculated as the Second Moment of Area (I) of the entire midship section about its horizontal neutral axis, divided by the distance to the deck or keel (whichever is smaller). Z = I / y_max. | The contribution of an L-angle stiffener to the hull’s ‘I’ is: I_angle = A_angle * d², where A is its cross-sectional area and d is the distance from the hull’s neutral axis to the angle’s own centroid. This shows that stiffeners placed farther from the neutral axis (e.g., high on the deck or deep on the keel) contribute much more to the hull’s strength. |

| Classification Society Rule | Societies like BV, ABS set a minimum required section modulus (Z_min) based on the ship’s dimensions (length, breadth, depth). The actual hull’s modulus must be equal to or greater than Z_min. | The structural design must arrange enough steel in the right places to meet Z_min. Using higher-strength steel (AH36 vs. Grade A) can reduce the required area, allowing for weight savings. |

| Importance for Cargo Capacity | The hull’s ability to resist bending moments limits how much cargo can be loaded. The "still water bending moment" from cargo must be within the capacity provided by the hull section modulus and the steel’s allowable stress. | This is a direct commercial impact. A stronger hull (higher Z) can safely carry more cargo, increasing the ship’s earning potential. |

This global calculation directly influences the local design. If the hull needs more strength, the naval architect might specify thicker deck plates, or more importantly, add more or larger longitudinal stiffeners. This is where the choice of L-angle size becomes critical. A larger angle (e.g., L200x100x12 vs. L150x100x10) has a larger cross-sectional area (A) and a higher local section modulus for its own bending. But for the hull modulus, its distance (d) from the ship’s neutral axis is often the dominant factor.

When we supply L-shaped steel for shipbuilding, we are providing components that feed into this global calculation. Our consistent quality and dimensions ensure that the theoretical ‘A’ and calculated ‘d’ used by the designer match the real parts installed. Any deviation in size could, in a worst-case scenario, reduce the actual hull modulus below the required minimum, putting the vessel’s class certification at risk.

What is the radius of gyration1 L section?

A designer chooses an L-angle for a column in a ship’s accommodation block. He checks its strength against buckling. The key property for this check is not the section modulus, but the radius of gyration1. Ignoring this can lead to sudden, catastrophic failure.

The radius of gyration1 (r) for an L-section2 is a measure of how its cross-sectional area3 is distributed relative to a given axis. It is calculated as the square root of (I / A), where I is the second moment of area and A is the cross-sectional area3. It determines the section’s resistance to buckling.

While section modulus (Z) rules for bending, the radius of gyration (r) is the king for compression members prone to buckling. A long, slender column made of L-angle steel will fail by buckling long before the steel reaches its compressive yield strength. The value of ‘r’ tells you how slender the column is.

The Role of Radius of Gyration in Structural Design

| Aspect | Explanation | Calculation for L-Sections |

|---|---|---|

| Definition & Formula | Radius of Gyration, r = √(I / A). I = Second moment of area about a specific axis. A = Cross-sectional area. |

You calculate r_x for buckling about the x-axis (usually parallel to one leg) and r_y for the y-axis. For L-angles, these two values are different. |

| Physical Meaning | It is the hypothetical distance from the axis at which the entire area could be concentrated and still have the same moment of inertia4. A higher ‘r’ means the area is spread farther from the axis, making the section stiffer and more resistant to buckling. | For an equal L-angle, the minimum r is about the axis at 45 degrees to the legs (the "weak" axis). This is often the critical value for design. |

| Link to Slenderness Ratio | The slenderness ratio5 (λ) = Effective Length (L_e) / r. This is the most important parameter for buckling calculations. A lower λ (shorter column or higher r) means much higher buckling resistance6. | Designers choose an L-angle size that provides a sufficiently large ‘r’ to keep the slenderness ratio5 below the allowable limit for the given column length and end conditions. |

| Practical Implication for L-Angles | L-angles are common in compression: as struts in trusses, pillars, and stiffeners. Because their area is not symmetrically distributed, they have different r values about different axes and can buckle in a twisting mode (torsional-flexural buckling). | This is a key disadvantage of single-angle compression members. Often, two angles are bolted or welded together back-to-back to form a "starred" section with a much higher and more uniform radius of gyration1. |

For a fabricator or buyer, understanding this concept helps when reading design specifications. If a drawing calls for an L100x100x10 angle as a strut with a maximum unsupported length of 3 meters, that specification is based on a buckling check using the radius of gyration1. Substituting a thinner angle (e.g., L100x100x8) might have nearly the same cross-sectional area3 but a significantly lower ‘r’, making it unsafe for that length.

This technical depth is part of our service. When a client like a project contractor in the Philippines needs L-angles for a specific structural application, we can provide not just the material, but also the standard mechanical property tables that include the cross-sectional area3 (A), moment of inertia4 (I), section modulus (Z), and radius of gyration1 (r) for each size. This data empowers their engineers. Our guarantee of dimensional accuracy ensures that the real part performs exactly as the table predicts.

How does shape affect section modulus?

You need a stiffener with a section modulus of 50 cm³. You can use a heavy L-angle or a lighter bulb flat. The shape decides which one is more efficient. Choosing the wrong shape wastes steel and adds unnecessary weight to the vessel.

The shape dramatically affects the section modulus by determining how the material is distributed relative to the neutral axis. Shapes that concentrate material far from the neutral axis (like I-beams or bulb flats) achieve a much higher section modulus per unit weight than compact shapes like solid bars or small angles.

This is the core idea behind structural engineering: efficiency. You want the maximum strength (or stiffness) for the minimum amount of material. The section modulus (Z) is the measure of bending strength. So, we want to maximize Z while minimizing the cross-sectional area (A), which is directly related to weight and cost.

Analyzing How Different Shapes Achieve Bending Efficiency

| Shape Example | Material Distribution | Effect on Section Modulus (Z) | Efficiency (Z/A Ratio) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Square Bar | Material is concentrated close to the centroid. | The Second Moment of Area (I) is relatively low because most material is near the axis. Z is moderate. | Low. You use a lot of heavy material for a given bending strength. This is inefficient for beams. |

| L-Angle (Unequal) | Material is distributed along two legs, but still relatively close together. The centroid is near the corner. | I and Z are higher than a solid bar of the same area because the legs push some material farther out. However, Z is different about the two principal axes. | Moderate. Better than a solid bar, but not optimal. It is a good general-purpose bracket and stiffener. |

| I-Beam (or H-Beam) | Most material is concentrated in the two flanges, which are far from the neutral axis. The thin web connects them. | This is a highly efficient shape for bending in one direction (strong axis). The flanges, being far from the neutral axis, contribute massively to I and Z. | Very High. This is why I-beams are standard for land-based construction. For ships, they are used in large girders. |

| Bulb Flat Steel | This is the marine-optimized shape. It has a flat web and a bulb (rounded edge) at the tip. The bulb puts extra material at the farthest possible point. | Extremely efficient for unidirectional bending as a stiffener attached to a plate. The plate acts as the second flange, and the bulb provides the distant material. | Highest for marine stiffeners. This is the preferred choice for ship hull longitudinal and transverse stiffeners. It provides the required Z with minimal weight. |

The formula I = ∫ y² dA explains everything. The term y² means that the contribution of a small area (dA) to the moment of inertia increases with the square of its distance (y) from the neutral axis. So, moving a small amount of material twice as far away makes it four times more effective at resisting bending.

This is why bulb flats often replace L-angles for primary hull stiffeners. When Gulf Metal Solutions mentioned their next order for "spherical flat steel" (bulb flats), it was for this reason. For the same bending strength (Z), a bulb flat stiffener weighs less than an L-angle stiffener. Less weight means more cargo capacity or better fuel efficiency for the ship.

As a supplier, we provide both L-shaped steel and bulb flat steel. Our role is to understand the application. If a client needs angles for brackets, gussets, or secondary framing, we recommend L-sections. If they need efficient, primary longitudinal stiffeners for a hull or deck, we recommend bulb flats. This informed guidance, based on how shape affects performance, helps our clients build better, more efficient ships. It transforms us from a simple vendor into a technical partner in their supply chain.

Conclusion

Mastering section modulus calculation equips you to validate designs and select optimal sections. It connects the math to the metal, ensuring every piece of L-shaped steel in your ship earns its place.

-

Understanding the radius of gyration is crucial for ensuring structural integrity and preventing buckling in design. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Exploring L-section properties helps in selecting the right materials for construction, enhancing safety and performance. ↩

-

The cross-sectional area directly impacts load-bearing capacity; understanding it is essential for safe design. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Moment of inertia is key in calculating resistance to bending and buckling; knowing it aids in effective design. ↩ ↩

-

The slenderness ratio is vital for predicting buckling behavior; understanding it can improve design safety. ↩ ↩

-

Learn about buckling resistance to ensure your designs can withstand compressive forces without failure. ↩