In shipbuilding, a tolerance mismatch of just a few millimeters on an L-angle can cause hours of costly rework, delay an entire block assembly, and compromise structural integrity.

Marine L-shaped steel must adhere to strict dimensional tolerances for leg length, thickness, straightness, and squareness as per standards like EN 10056 or ASTM A6. This accuracy ensures proper fit-up during automated fabrication, maintains structural alignment, and guarantees predictable load paths in the finished vessel.

I’ve seen shipyards in Vietnam stop production because a batch of angles was out of tolerance. The ripple effect on schedule and cost is massive. This article explains the precise tolerances required and why they are non-negotiable for efficient marine construction.

What is the L shape steel connection?

The connection is where the L-angle transfers load to the rest of the structure. A poorly designed or executed connection is the weakest link, regardless of how accurate the angle itself is.

L-shaped steel connections1 are typically made by welding one leg to a plate or another member. Common types include fillet welds along the leg edge, slot welds, or bolted connections using cleats. The design must account for load eccentricity and potential torsion introduced by the angle’s geometry.

Think of the connection as the handshake between components. It must be strong and precise. The tolerance of the angle directly influences how easy or difficult it is to make a good connection.

Design and Fabrication Challenges of Angle Connections

Connecting an L-angle is not as simple as connecting an I-beam. Its asymmetric shape creates unique challenges that tolerance control helps to manage.

1. Types of Connections in Marine Construction:

- Continuous Fillet Weld2: This is the most common method. One leg of the angle is welded continuously to a plate (e.g., a stiffener welded to a hull plate). The weld is placed along the toe of the connected leg. Tolerance in the angle’s leg straightness and squareness is critical here. If the angle is bowed or twisted, it will not sit flush against the plate, creating a gap. This gap leads to poor weld penetration, stress concentrations, and potential weld cracking.

- Intermittent Fillet Weld3: Used to save welding time and material on less critical stiffeners. The same tolerance requirements apply.

- Bolted Connections4: L-angles are often used as connection angles or cleats to bolt beams to columns or to connect prefabricated modules. Holes are drilled in both legs. The accuracy of the hole pattern and the flatness of the leg surfaces are vital. If the leg is not flat, the bolt will not tighten evenly, creating a loose connection.

- Brackets and Gussets: L-angles are cut and welded to form custom brackets. The accuracy of the cut length and angle (usually 90 degrees) determines how well the bracket fits into its designated space.

2. The Eccentricity Problem:

This is the core engineering challenge. When you connect only one leg of an L-angle, the load path does not pass through the center of gravity of the angle section. This creates an eccentric moment (a twisting force). Designers must calculate this moment and ensure the weld or bolts can resist it. Dimensional inaccuracy magnifies this eccentricity, creating uncalculated stresses.

3. How Dimensional Accuracy5 Solves Connection Problems:

- Consistent Leg Thickness: If the leg thickness varies beyond tolerance, the weld throat size becomes inconsistent. A thinner leg means a smaller, weaker weld.

- Sharp and Square Root (Heel): The inside corner should be a clean 90-degree angle. If it is rounded or filled, the angle cannot sit properly into a corner bracket or against two perpendicular plates.

- Leg Straightness6: A straight leg makes full contact along the entire weld length. A curved leg only touches at points, requiring the fitter to force it straight with jacks or wedges before welding—this induces unwanted residual stresses.

Practical Example from a Shipyard:

A shipyard in the Philippines fabricates side shell panels. They weld hundreds of vertical L-angle stiffeners to the outer hull plate. They use automated welding robots. The robot program assumes every angle is straight and has legs of exact dimensions. If a batch of angles has a leg length tolerance of +3mm instead of the specified ±1.5mm, the robot’s welding torch will be misaligned. This causes bad welds or forces the yard to stop and manually adjust every single angle, destroying their production efficiency. This is why they insist on certified angles from suppliers who understand and control these tolerances.

What is the verticality tolerance1 for steel columns table?

While L-angles are rarely primary columns, the concept of verticality tolerance1 is part of a broader family of geometric tolerances that apply to all steel sections, including how an L-angle is used as a vertical member or brace.

There is no single universal table; verticality tolerance1 depends on the project specification and relevant standard (e.g., AISC, EN 1090). For building columns, a common tolerance is height/1000 but not more than 25mm. For marine structures, tighter tolerances often apply due to dynamic loading and integration with complex systems.

In marine construction, we talk about "straightness" and "squareness" for angles more than "verticality." But the principle is the same: how much deviation from the perfect intended shape is allowed before it affects strength or assembly.

Understanding Straightness and Alignment Tolerances for Marine Sections

For L-angles used as stiffeners or framing, their straightness is the equivalent of a column’s verticality. It determines how true they line up.

1. Straightness Tolerance for L-Angles:

This is defined in the product standard. For example, EN 10056-12 specifies straightness tolerance3 based on the length of the angle.

- The deviation from straightness (sweep or bow) over any 2m length is typically limited to 2mm.

- The overall straightness over the total length (L) is limited to *0.0015 L*, with a minimum of 5mm.

This means a 12-meter-long angle bar is allowed to have a maximum bow of 18mm (0.0015 12000mm). For precision applications, a tighter tolerance can be specified.

2. Consequences of Poor Straightness in Marine Contexts:

- Fit-Up Problems: A bowed angle will not align with pre-drilled holes or other connecting members. Fitters must use force to pull it into position, inducing "lock-up" stresses.

- Weld Gap Issues: As mentioned, a gap between the angle leg and the plate leads to poor weld quality.

- Aesthetic and Functional Issues: For visible elements like handrail posts or door frames, a visibly crooked member is unacceptable.

- Weight Distribution: In a row of deck stiffeners, if some are bowed, they may not share the load evenly, overstressing the straight ones.

3. Twist Tolerance:

This is another critical geometric tolerance. Twist is when one end of the angle is rotated relative to the other, like a propeller. Standards also limit this. Excessive twist makes it impossible for both legs to make contact with reference surfaces.

4. How Mills Control Straightness:

After hot-rolling, angles pass through a straightening machine (often a series of rolls). The skill of the mill operator and the calibration of this machine determine the final straightness. High-quality mills have automated systems for consistent results. When we audit our partner mills, we check the capability of their straightening process. This is a key part of ensuring "quality consistency4," which was a major pain point for buyers like Gulf Metal Solutions.

5. Specifying Tighter Tolerances:

For critical applications, you can specify a tolerance stricter than the standard. For example:

- "Straightness shall not exceed 1mm per meter and 10mm over total length."

- "No visible sweep or twist."

This specification will increase the cost, as the mill may need to perform additional sorting and re-straightening, and the yield from the production run will be lower.

What are the standard steel sections used in shipbuilding?

Shipbuilding uses a specialized set of steel sections optimized for curved hulls, efficient stiffening, and assembly. L-angles are a key member of this family, but they are not used alone.

The standard steel sections in shipbuilding are plates (for hull shell and decks), bulb flat steel (the primary stiffener), angle bars (L-shaped steel for frames and brackets), tee bars (for stronger stiffeners), and flat bars. These profiles are designed for efficient welding and optimal strength-to-weight ratio in a marine environment.

Each section has a specific role. Using the wrong section is inefficient and can weaken the ship. Let’s look at the full team and how they work together.

The Shipbuilding Steel Section Family and Their Roles

Modern ship design software has libraries of these standard sections. Their dimensions and properties are well-known to naval architects.

1. Bulb Flat Steel1 (BP):

This is the most characteristic shipbuilding section.

- Profile: It looks like a flat bar with a bulb (rounded protrusion) along one edge.

- Purpose: It is the default stiffener for hull plates, decks, and bulkheads. The bulb adds significant moment of inertia (resistance to bending) with a small increase in weight and material compared to a simple flat bar. It is more efficient.

- Orientation: It is always welded with the bulb facing away from the plate (the "free edge"). This placement offers the best resistance to buckling.

- Sizing: Designated by its height x thickness (e.g., BP 300×12). The bulb size is standardized.

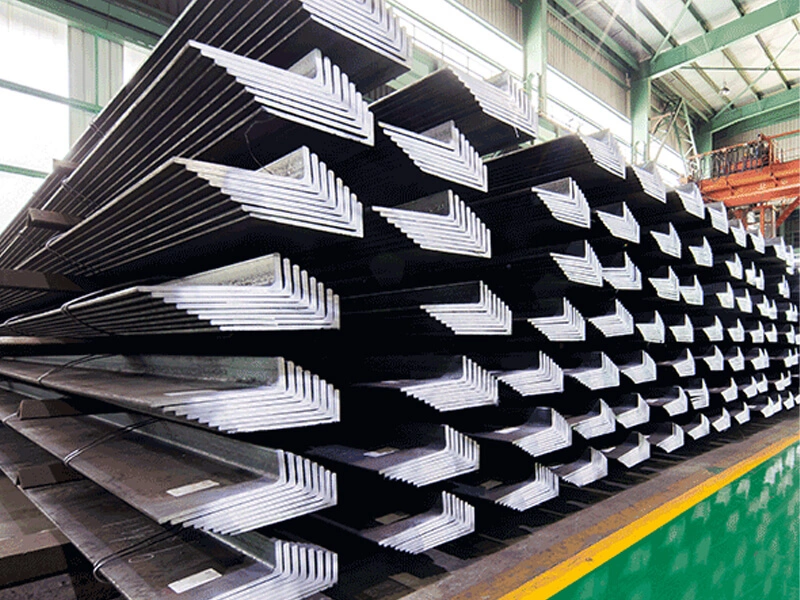

2. Angle Bar2 (L-Shaped Steel):

- Profile: The familiar 90-degree angle.

- Purpose: Used for secondary framing where bulb flats are not required, for brackets and gussets, and for door/window frames and handrail supports. They are also used as horizontal stringers on the hull. Unequal leg angles are common for specific applications where one leg needs to be longer for welding.

- Profile: Looks like the letter "T".

- Purpose: Used for stronger stiffeners than bulb flats, often at key locations like the centerline girder of the ship’s bottom or under major deck openings. It provides great strength in one direction.

- Profile: A simple rectangular bar.

- Purpose: Used for small stiffeners, edge reinforcements, connecting plates, and wear strips. It is the simplest and cheapest section.

- L-shaped section steel: This can sometimes refer to an asymmetrical angle or a custom profile designed for a specific ship part.

Tolerance Requirements Across Sections:

All these sections require tight dimensional control, but for different reasons.

- Bulb Flats: The height and bulb geometry must be consistent for automatic welding and fair hull curves.

- Angles: Leg length and straightness are critical for fit-up.

- Tee Bar3s: The alignment of the web and flange must be precise.

The shipyard receives these sections and often cuts them to length using automated lines. If the incoming material is not within tolerance, the automated process fails. This is why shipyards are among the most demanding customers for dimensional accuracy. They value suppliers who can provide SGS inspection reports6 that include verification of critical dimensions, not just chemical and mechanical properties.

Which type of steel is most commonly used in shipbuilding due to its strength and durability?

The workhorse steel for shipbuilding is not a fancy, exotic alloy. It is a family of high-strength, fine-grained steels with tightly controlled properties that balance strength, toughness, weldability, and cost—exactly what a massive, welded structure like a ship requires.

The most commonly used steel in shipbuilding is Normal Strength (Grade A)1 and Higher Strength (Grades AH, DH, EH)2 structural steel per the ASTM A1313 / ABS / DNV GL rules. Grade AH36 is a global standard for its optimal balance of 36 ksi yield strength4, good toughness, and excellent weldability for most hull structures.

When I talk to shipyards in Thailand or Pakistan, "AH36" is the default language. It’s the baseline from which they specify up for more demanding areas or down for non-critical parts. Its dominance is a result of decades of naval architecture evolution.

The Shipbuilding Steel Grades: A Hierarchy for Different Demands

Ship steel is categorized by its yield strength4 and its impact toughness5 (resistance to brittle fracture).

1. The Grading System (ASTM A1313 / IACS Unified Requirements):

- Letter (A, B, D, E): This indicates the impact toughness5 testing temperature.

- A: Tested at room temperature. (Basic grade)

- B: Tested at 0°C.

- D: Tested at -20°C.

- E: Tested at -40°C.

- Number (32, 36, 40): This indicates the minimum yield strength4 in ksi (kilo-pounds per square inch).

- 32: 32 ksi yield (≈220 MPa)

- 36: 36 ksi yield (≈250 MPa) – The most common.

- 40: 40 ksi yield (≈275 MPa)

2. Most Common Grades and Their Applications:

- Grade A / Grade B: Normal strength steel. Used for non-critical internal structures, secondary bulkheads, and areas with low stress in temperate waters.

- Grade AH36 / DH36 / EH36: These are the Higher Strength workhorses.

- AH36: Used for the majority of the hull structure (shell plating, decks, bulkheads) in commercial vessels trading in most global waters. It offers a good upgrade in strength over Grade A without a severe cost or weldability penalty.

- DH36: Used for vessels operating in colder climates (e.g., North Atlantic, Arctic supply vessels) where -20°C toughness is required.

- EH36: For the most demanding Arctic service or for critical areas like the sheer strake (top side shell) on large container ships.

3. Why AH36 and Similar Grades are So Common:

- Proven Performance: Decades of use have proven its reliability.

- Excellent Weldability: Its chemical composition is controlled to have a low Carbon Equivalent (CEV)6, allowing for high-deposition, high-speed welding without pre-heat in most thicknesses. This is crucial for shipyard productivity.

- Wide Availability: Every major steel mill in the world that serves shipyards produces these grades. This keeps competition high and prices stable.

- Class Society Approval: AH36/DH36/EH36 are universally approved by all classification societies (ABS, DNV, LR, ClassNK, etc.). This is essential for getting the ship certified.

4. From Plates to Sections:

The same grade philosophy applies to sections.

- The L-shaped steel used for ship frames and brackets is typically AH36 or DH36 angle bar.

- Bulb flat steel is also supplied in these grades.

This material consistency is important. It means the shipyard can use the same welding procedures and consumables for plates and sections, simplifying operations.

The Role of Tolerances in This Context:

Even the best AH36 steel is useless if it is not formed accurately. The dimensional tolerances7 for plates (flatness, thickness) and sections (straightness, leg dimensions) are specified in separate standards but are equally part of the material specification. A mill producing to AH36 must control both the metallurgical properties (strength, toughness) and the geometric properties (dimensions, shape). Supplying steel that meets both sets of requirements is what defines a true marine steel supplier8.

Conclusion

Marine L-shaped steel requires precise dimensional tolerances for proper connections and assembly. It is part of a standardized family of shipbuilding sections, most commonly made from grades like AH36, where controlled geometry is as critical as controlled chemistry.

-

Understanding Grade A’s applications helps in recognizing its role in shipbuilding and structural integrity. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore how these grades enhance ship performance and safety in various marine environments. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about the ASTM A131 standard to understand the quality and specifications of shipbuilding steel. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover the importance of yield strength in ensuring the durability and safety of ships. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understanding impact toughness is crucial for assessing a ship’s resilience in harsh conditions. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore how CEV influences weldability and overall performance of shipbuilding materials. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn how precise tolerances ensure the structural integrity and safety of ships. ↩

-

Understanding the criteria for marine steel suppliers helps in selecting reliable sources for shipbuilding materials. ↩