Picture a ship’s frame giving way in a storm. The cause is often traced back to a single batch of uncertified steel with hidden weaknesses. For L-shaped steel, a critical component in shipbuilding, a piece of paper—the certification—is your only real guarantee of safety and performance. Without it, you are building on a gamble.

Certification for Marine L-Shaped Steel is a non-negotiable requirement. It is an official document from a recognized classification society (like ABS, DNV, or LR) that verifies the steel’s chemical composition, mechanical properties (strength, toughness), and manufacturing process meet strict maritime standards. This certification ensures the steel can withstand harsh sea conditions, including high dynamic loads and corrosive environments, guaranteeing the structural integrity of the vessel’s frames, brackets, and stiffeners.

You now see why certification is the foundation. But to truly appreciate its value, you must understand what it certifies. The certification is a promise about the steel’s quality. To decode that promise, we need to explore the specific grades, standards, and types of steel it covers. The following questions will dissect the meaning behind "marine grade" and show you exactly what you are paying for.

What does marine grade stainless steel mean?

You see the term "marine grade" on many products. For stainless steel, it often carries a hefty price premium. Is this just a marketing term, or does it signify a real, critical difference? Using the wrong stainless steel in a marine application can lead to rapid, unexpected failure.

"Marine grade stainless steel" specifically refers to alloys, primarily Type 316 and its low-carbon variant 316L, which contain 2-3% Molybdenum (Mo). This added element dramatically increases resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion caused by chloride ions in seawater. While other stainless steels like 304 may survive, 316/L is the recognized standard for reliable, long-term performance in harsh marine environments for components like fittings, railings, and fasteners.

The term "marine grade" is precise for stainless steel. It points to a specific chemical recipe designed to fight a specific enemy: salt. To understand its importance, we need to look at the science of corrosion and the practical implications for your project.

The Chemistry of Survival in Seawater

Ordinary stainless steel works by forming a passive chromium oxide layer. Seawater, rich in chlorides, attacks and breaks down this layer.

- The Role of Molybdenum: In 316 stainless steel, molybdenum integrates into the passive layer. It makes this layer much more stable and resistant to chloride attack. It essentially "armors" the steel’s natural shield.

- The Danger of "General Grade" Stainless: Type 304 stainless lacks molybdenum. In mild or intermittent exposure, it may be fine. In constant splash, immersion, or salt-laden air, its passive layer is more easily breached, leading to localized pitting corrosion.

Defining "Marine Grade" in Practice

Let’s break down what "marine grade" means across different aspects of specification and use.

| Aspect of "Marine Grade" | What It Means for Stainless Steel | Consequence of Using a Non-Maritime Grade |

|---|---|---|

| Core Alloy Designation | Primarily AISI 316 or AISI 316L. The "L" denotes low carbon, which improves weldability and reduces susceptibility to sensitization (carbide precipitation). | Using 304 in the same application can lead to deep pits, perforation, and stress corrosion cracking over time, especially in welded areas or crevices. |

| Key Alloying Element | Molybdenum (Mo) content of 2-3%. This is the defining feature that justifies the "marine grade" label and its higher cost. | Without Mo, the steel’s corrosion resistance in chlorides is significantly lower. The initial material savings are quickly erased by repair and replacement costs. |

| Common Marine Applications | Through-hull fittings, propeller shafts, deck hardware, railings, cleats, fasteners, pumps, and valves on ships and offshore platforms. | These are critical components. Failure here can lead to water ingress, equipment malfunction, or loss of overboard equipment. |

| Certification & Standards | Material should be supplied with a mill test certificate (MTC) verifying the chemical composition meets 316/316L standards, often per ASTM A240 or equivalent. | Lack of proper certification means you cannot verify the Mo content. You might be paying for 316 but receiving 304, with no way to prove it until it fails. |

From my experience dealing with project contractors in the Philippines and Qatar, specifying "marine grade stainless" is only the first step. The second, crucial step is verification. We once had a client who received "316" bolts from another source that rusted within months. They provided the MTC, and the chemistry was off—the molybdenum was at the very bottom of the allowable range, borderline 304. This is why, for clients like Gulf Metal Solutions, we emphasize supporting third-party inspection like SGS. The certificate is not just paperwork; it is a verifiable record that the "marine grade" steel you ordered is the "marine grade" steel you received, with the right chemistry to do its job for decades.

What are the grades of marine steel plates?

You need to order plates for a ship’s hull. The supplier asks, "What grade?" The alphabet soup of AH32, DH36, EH40 can be confusing. Choosing the wrong grade can mean your plates are too weak, too brittle, or impossible to get approved by the ship’s classification society.

Marine steel plate grades are standardized codes defined by international classification societies like ABS, DNV, and Lloyd’s Register. The most common series is the "H" grades: AH, DH, EH, FH. The letter indicates notch toughness (resistance to brittle fracture) at low temperatures, and the number indicates the minimum yield strength in ksi (e.g., 36 = 36 ksi or 355 MPa). For example, DH36 is a common grade with good toughness for most ocean-going vessels.

Understanding these grade codes is essential for communication and compliance. Each part of the code tells you something vital about the steel’s performance under the stresses of the sea.

Decoding the Grade Naming System

The grade is a compact summary of the steel’s key mechanical properties.

- The Strength Number (32, 36, 40, etc.): This is the minimum yield strength. A higher number means the steel can withstand greater forces before it starts to permanently deform. It allows for thinner, lighter structures.

- The Toughness Letter (A, D, E, F): This is arguably more critical. It specifies the Charpy V-Notch impact test temperature. It tells you how well the steel resists brittle fracture in cold conditions.

A Guide to Common Marine Plate Grades

This table explains the typical grades you will encounter and where they are used.

| Steel Grade | Key Properties Explained | Typical Applications in Shipbuilding | Why This Grade is Chosen |

|---|---|---|---|

| AH32 / AH36 | A = Minimum impact tested at 0°C (32°F). H = High tensile. 36 = 355 MPa yield strength. Good general toughness for temperate waters. | Internal structures, upper decks, and bulkheads in vessels not operating in very cold climates. | A cost-effective choice for areas of the ship that experience less severe dynamic loading and warmer operating temperatures. |

| DH32 / DH36 | D = Impact tested at -20°C (-4°F). Better low-temperature toughness than A-grade. | The most common grade for hull plating, main frames, and critical structures of most cargo ships, tankers, and bulk carriers in international service. | It offers an excellent balance of strength, toughness, weldability, and cost. Suitable for most ocean environments. |

| EH32 / EH36 / EH40 | E = Impact tested at -40°C (-40°F). High toughness for Arctic or low-temperature service. | Hull plating and critical components for ice-class vessels, LNG carriers, and ships operating in polar regions. | Essential where exposure to extremely cold air and water poses a high risk of brittle fracture. |

| FH32 / FH40 | F = Impact tested at -60°C (-76°F). Extraordinary toughness for the most severe conditions. | Specialized vessels for extreme Arctic exploration, offshore structures in the worst environments. | Used when the design specifically calls for the highest possible fracture toughness at the lowest temperatures. |

When a client from Romania or Thailand contacts us for Marine Steel Plates, our first technical question is always about the required grade and the classification society (ABS, DNV, LR, etc.). This is not a formality. A plate stamped "DH36" from one mill for ABS is not automatically approved for a DNV GL project without the proper DNV certification. The grade is part of a package that includes the mill’s approval from that specific society. Our long-term cooperation with certified mills ensures we can provide these plates with the correct, traceable certification for your project’s specific society. This eliminates a major risk: sourcing plates that meet the grade chemically and mechanically but lack the proper approval stamps, causing rejection at the shipyard.

What is marine grade structural steel?

Beyond plates, the entire skeleton of a ship uses structural shapes. Calling it "marine grade" means it must do more than just hold weight. It must fight fatigue, resist corrosion, and absorb massive shocks without failing.

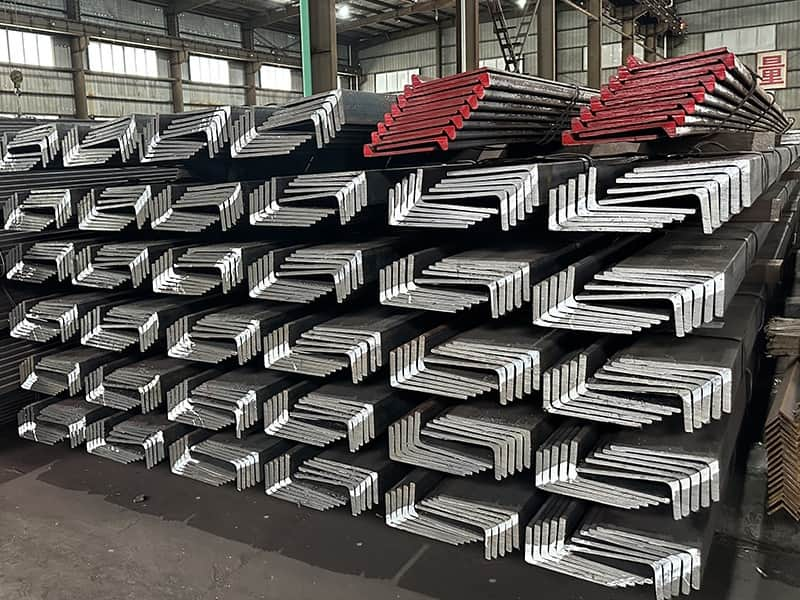

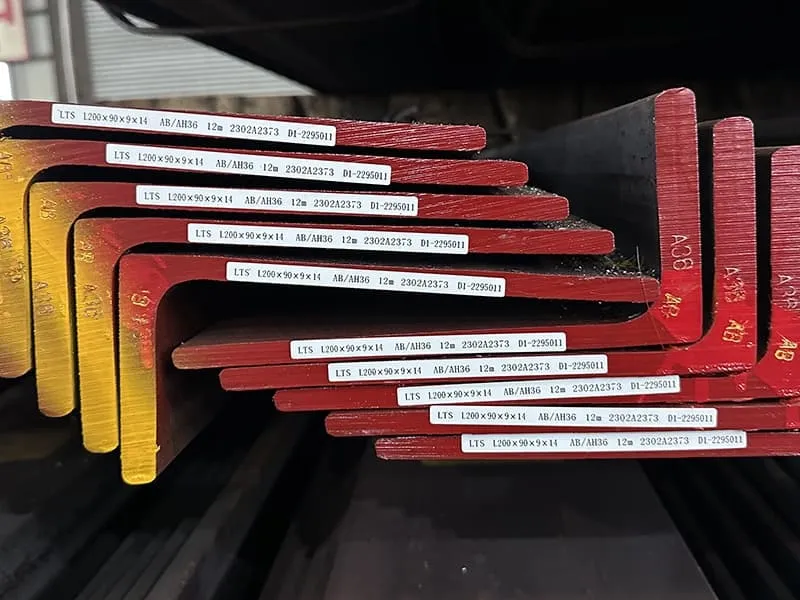

Marine grade structural steel refers to shaped sections—like L-shaped steel (angles), bulb flats, and I-beams—that are manufactured from certified marine-grade plates (e.g., AH36, DH36) and are themselves certified by a classification society. This certification ensures the entire profile, not just the base material, maintains the required strength, toughness, and weldability throughout its cross-section, making it fit for purpose in ship frames, stiffeners, and brackets.

It is a mistake to think you can buy certified plate and then simply roll it into an angle without losing the certification. The forming process itself can affect the material’s properties. "Marine grade" for structural steel implies control over the entire manufacturing chain.

From Plate to Profile: Maintaining Integrity

The journey from a steel plate to a finished L-angle is a critical phase where quality must be preserved.

- Certified Input Material: The process starts with a hot-rolled plate that already has full certification (MTC) for its marine grade (e.g., DH36).

- Controlled Forming Process: The plate is then heated and passed through rollers to form the L-shape. This process must be controlled to avoid damaging the steel’s microstructure.

- Final Product Certification: The finished L-shaped steel receives its own certificate. This certifies that the final product, as a shaped section, still meets all the mechanical and chemical requirements of the original grade.

The Specifics of Marine Structural Steel Shapes

Here’s a look at common marine structural shapes and what makes them "marine grade."

| Structural Shape | Common Marine Applications | Why Certification is Critical for This Shape |

|---|---|---|

| L-Shaped Steel (Angle Bar) | Ship frames, brackets, stiffeners, hatch coamings. Used to connect plates and provide lateral support. | Angles experience complex stress from multiple directions. Certification guarantees consistent properties along both legs and in the corner radius, which is a potential stress concentration point. |

| Bulb Flat Steel | Primary stiffeners for hull plating, decks, and bulkheads. The bulb provides efficient resistance to bending. | The forming of the bulb must not create weaknesses. Certification ensures the yield strength and toughness are uniform across the entire profile, including the bulb. |

| Flat Bars | Small stiffeners, backing bars, and various fabrication uses. | Often used in critical joinery. They must be cut from certified plate and carry their own traceable documentation. |

| Welded Profiles | Custom-built large beams or girders for special parts of the vessel. | These are fabricated from certified plates and sections. The weld procedure and filler metals must also be approved to maintain the "marine grade" status of the assembly. |

This point is vital for bulk buyers of sections like Marine Angle Steel. You are not just buying a shape; you are buying a certified component. A project contractor in Saudi Arabia building a series of barges cannot use ordinary structural angle from a local warehouse. The classification society surveyor will demand to see the mill certificates for every batch of L-shaped steel used in the hull framing. Without it, the work may be stopped. Our role is to supply these certified profiles directly from mills that are approved to produce them, complete with all the necessary documentation. This turns a potential project-stopping problem into a simple line item on a packing list.

What are the 4 types of steel?

This basic question is the foundation for all the others. Knowing the four main types helps you understand where "marine grade" fits in the bigger picture. It explains why we use different steels for different parts of a ship.

The four main types of steel, categorized by their chemical composition and microstructure, are: 1) Carbon Steel (little to no alloy, most common), 2) Alloy Steel (added elements like Cr, Ni, Mo for strength/hardness), 3) Stainless Steel (high Cr/Ni for corrosion resistance), and 4) Tool Steel (very hard, for cutting and shaping). Marine applications primarily use specific grades within Carbon Steel (marine-grade plates) and Stainless Steel (316), with some use of Alloy Steels for special purposes.

This classification is fundamental. It helps you understand why a ship’s hull (carbon steel) and its propeller shaft (stainless or special alloy steel) are made from completely different materials. Each type has a core purpose.

Understanding the Four Families

Each type is defined by what is added to the iron and how it is processed.

- Carbon Steel: This is the workhorse. Its properties are controlled mainly by the carbon content and heat treatment. It is strong and cheap but will rust without protection.

- Alloy Steel: Here, other elements are added in larger amounts to change the steel’s properties in specific ways, like increasing hardenability or strength.

- Stainless Steel: This is a specialized subgroup of alloy steel, defined by very high Chromium content (min. 10.5%) for corrosion resistance.

- Tool Steel: These are ultra-hard, wear-resistant steels designed to cut, shape, or form other materials.

How Each Type Relates to Marine Engineering

Let’s map these four types to their real-world roles in shipbuilding and marine structures.

| Steel Type | Primary Characteristic | Common Marine Examples & Notes | Relevance to Certification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Steel | Properties dominated by carbon content. Economical, strong, weldable, but corrodes easily. | Marine Plates & Sections (AH/DH/EH grades): The hull, deck, frames. Always used with protective coatings and cathodic protection. | Heavily Certified. Must meet exact chemical limits and mechanical property rules set by classification societies. |

| Alloy Steel | Added elements (e.g., Mn, Si, Cr, Mo, V) enhance strength, toughness, or hardenability. | Special Shafts, Gears, High-Strength Fasteners: May be used in propulsion systems or for critical, highly stressed mechanical parts. | Often requires specific material certifications and testing for the application, though not always a "marine" class society certificate. |

| Stainless Steel | High Chromium (& often Nickel) content creates a passive, corrosion-resistant oxide layer. | Type 316/L: Fittings, rails, pumps, components in corrosive zones. Duplex (2205): For more demanding offshore applications. | Certified to ASTM or EN standards verifying chemistry (esp. Cr, Ni, Mo). For critical parts, class society approval may also be needed. |

| Tool Steel | Very high hardness and wear resistance. Used for cutting, drilling, and forming tools. | Drill Bits, Cutting Blades, Die Components: Used in the shipyard for fabrication and repair, not typically in the ship’s permanent structure. | Not relevant for marine structural certification. Certified to tool steel industry standards. |

For a rational, results-driven buyer, this framework is power. It tells you that when you are sourcing L-shaped section steel for ship frames, you are dealing with Carbon Steel of a very specific, certified grade. When you are sourcing material for onboard chemical piping, you are in the realm of Stainless Steel. The suppliers, the cost drivers, and the certification requirements for these two types are completely different. A professional supplier should be able to clearly communicate this distinction and provide the correct, certified product for each need. This clarity prevents costly mix-ups and ensures every kilogram of steel on your vessel is fit for its specific purpose.

Conclusion

Certification is the definitive language of safety and quality in marine steel. It translates vague terms like "marine grade" into verified, traceable properties for plates and shapes like L-steel, ensuring your vessel is built on a foundation of guaranteed performance.