Walk through a modern shipyard, and you’ll see mountains of steel plates, angles, and beams. But not all this steel is the same. Each piece is engineered for a specific role in the vessel’s anatomy. Using the wrong type can compromise the entire ship.

Ship construction primarily uses marine-grade carbon steel certified by classification societies like ABS, DNV, or LR. This includes ordinary strength grades (A, B, D, E) and high-strength grades (AH32, AH36, DH36) for hull structures. Stainless steel, aluminum, and other alloys are used selectively for fittings, superstructures, and special applications where corrosion resistance or weight savings are critical. The choice is a careful balance of strength, toughness, weldability, and cost.

For shipbuilders, naval architects, and material suppliers, understanding this material palette is fundamental. It dictates design, procurement, and ultimately, the safety and performance of the vessel. This guide will explain the primary steel types, their properties, and their specific roles in building a ship. Let’s start with the workhorse of the industry.

What type of steel is used in ship construction?

The hull of an ocean-going vessel faces a brutal combination of forces: crushing water pressure, constant flexing, impact from waves, and corrosive saltwater. Standard construction steel would fail here. The steel used is a specialized product.

The primary steel for ship construction is marine-grade carbon/manganese steel1, certified by classification societies2 (ABS, LR, DNV, BV). It is categorized into ordinary strength (Grades A, B, D, E) and high-strength (Grades AH32, AH36, DH36, EH36) steels, selected based on the hull location’s required strength, toughness, and operating temperature. These steels have controlled chemistry for weldability and must pass impact tests to prevent brittle fracture.

The Specialized World of Hull Steel

Marine steel is not a single formula but a family of materials designed to meet published rules. Its selection is a precise science.

1. Governance by Classification Societies:

Every commercial ship is built to the rules of a society like the American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) or Det Norske Veritas (DNV). These societies:

- Approve the steel mills that can produce the material.

- Define the exact chemical and mechanical requirements for each grade.

- Require Mill Test Certificates (MTCs)3 as proof of compliance for every batch of steel.

2. The Two Main Families and Their Designations:

- Ordinary Strength Steel: The grade is a letter (A, B, D, E) indicating toughness level.

- A: Basic grade for less critical areas.

- B: Standard for general hull plating.

- D & E: Progressively better toughness at lower temperatures (-20°C, -40°C). Used in the bow and for cold-environment vessels.

- High Strength Steel: The designation includes a letter and a number (e.g., AH36).

- The Letter (A, D, E): Still indicates the toughness level.

- The Number (32, 36, 40): Indicates the minimum yield strength in kgf/mm² (e.g., 36 = 355 MPa).

- Example: DH36: Means "D" toughness (tested at -20°C), "H" for High Strength, and 355 MPa yield strength.

3. Key Properties Beyond Strength:

- Toughness: The Charpy V-notch impact test4 is mandatory. It ensures the steel remains ductile in cold water, absorbing energy rather than cracking.

- Weldability: Controlled levels of Carbon, Sulfur, and Phosphorus, along with a calculated Carbon Equivalent (CE), ensure the steel can be welded extensively without cracking.

- Fatigue Resistance: The steel must withstand decades of cyclic loading from waves without developing cracks.

Application-Based Selection in a Typical Ship:

| Hull Structure Location | Typical Steel Grade | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Midship Bottom & Side Shell | AH36 or DH36 | High global bending stresses; high strength reduces weight. DH36 offers extra toughness. |

| Forward Bottom & Bow | DH36 or EH36 | Subject to wave slamming and lower temperatures; maximum toughness is critical. |

| Main Deck (Cargo Area) | AH36 | High strength to support heavy loads (containers, bulk cargo) with minimal structure. |

| Internal Bulkheads (non-critical) | Grade A or B | Lower stress application; cost efficiency is important. |

| Superstructure | Lower-strength grades or AH32 | Reducing weight high up improves ship stability; loads are lower. |

For suppliers like us, providing the correct type means sourcing from mills with the necessary society approvals and ensuring the MTCs match the ordered grade exactly. This is the "stable quality" our clients rely on. This specialized steel falls under one of the four broad categories of steel, which is our next topic.

What are the 4 types of steel?

Knowing the four basic types of steel provides a essential framework for understanding all steel products. A client in Vietnam was confused why stainless steel was so much more expensive than the "ship steel" we supplied. Placing them in these categories made it clear.

The four fundamental types of steel are Carbon Steel1, Alloy Steel2, Stainless Steel3, and Tool Steel4. Shipbuilding hulls are made primarily from Carbon Steel1 (specifically, high-strength low-alloy carbon steel5). Stainless Steel3 is used for specific marine fittings. Alloy and Tool Steel4s have niche applications in machinery. This classification is based on chemical composition and defining properties.

A Practical Guide to Steel Classifications

Each type has a distinct "recipe" and purpose. Your choice depends on whether you need strength, corrosion resistance, hardness, or a combination.

1. Carbon Steel1

This is the most common type, making up over 90% of all steel production. It is primarily iron with carbon as the main alloying element.

- Subcategories:

- Low Carbon (Mild Steel): 0.6% Carbon. Very hard and strong, but brittle. Used for knives, springs, wire.

- In Shipbuilding: Marine grades like ABS AH36 are high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) carbon steels. They have small, precise additions of elements like Niobium or Vanadium to increase strength, but they are still fundamentally carbon steels.

2. Alloy Steel2

This is carbon steel with significant additions of other elements like Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni), Molybdenum (Mo), or Vanadium (V) to enhance specific properties.

- Purpose: To increase strength, hardness, wear resistance, or toughness without requiring high carbon levels.

- Example: A common alloy steel is 4140 (with Chromium and Molybdenum). Note: Many people mistakenly call HSLA steels "alloy steels," but in formal classification, marine HSLA steels are still considered a subset of carbon steel.

3. Stainless Steel3

Defined by a minimum of 10.5% Chromium, which forms a passive oxide layer that resists corrosion.

- Key Marine Grades:

- 304 (18/8): General-purpose stainless.

- 316: Adds Molybdenum for superior resistance to chlorides (saltwater). The standard for marine hardware.

- Cost & Use: Stainless is 5-10 times more expensive than carbon steel. It is not used for primary hull structures.

4. Tool Steel4

Very hard, wear-resistant steels designed for cutting, drilling, and forming other materials. They contain high carbon and elements like Tungsten and Cobalt. Not used in structural applications.

Comparison Table for Clarity:

| Steel Type | Main Alloying Elements | Key Property | Cost Relative to Carbon Steel1 | Shipbuilding Use Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Steel1 (e.g., A36, AH36) | Iron, Carbon, Manganese. | High strength, good toughness, weldable. | 1x (Base Cost) | Hull plates, frames, stiffeners (95% of hull weight). |

| Alloy Steel2 (e.g., 4140) | Adds Cr, Mo, Ni. | High strength, hardenability. | 2x – 4x | Special shafts, gears in engine room (not hull). |

| Stainless Steel3 (e.g., 316) | Min. 10.5% Cr, plus Ni, Mo. | Excellent corrosion resistance. | 5x – 10x | Deck railings, cleats, some piping. |

| Tool Steel4 | High C, W, Co, V. | Extreme hardness, wear resistance. | 10x+ | Cutting tools in workshop. |

For a shipbuilder, carbon steel (in its marine HSLA form) is the clear choice for the hull. This brings up a common comparison: between mild steel (MS), a type of carbon steel, and stainless steel (SS).

Which is stronger, SS or MS?

This question needs refinement. "Stronger" can mean yield strength1, tensile strength, or hardness. And "MS" (Mild Steel) is just one form of carbon steel. A more accurate comparison is between standard structural carbon steel and common austenitic stainless steel. For hull frames, strength is paramount.

When comparing common grades, high-strength marine carbon steel2 (like AH36 with 355 MPa yield) is significantly stronger in terms of yield and tensile strength than common austenitic stainless steel (like 304 with ~205 MPa yield). However, some specially hardened stainless grades can be very strong. For ship hull structures, carbon steel provides the necessary strength at a fraction of the cost of stainless. Strength is not the primary reason for choosing stainless steel.

A Detailed Comparison of Mechanical Properties

We need to compare apples to apples: standard structural grades.

1. Yield Strength (The Design Strength):

This is the stress at which the material begins to deform permanently. It is the most important number for structural engineers.

- Mild Steel (ASTM A36)3: Minimum yield strength1 = 250 MPa.

- Marine Carbon Steel (ABS AH36)4: Minimum yield strength1 = 355 MPa.

- Austenitic Stainless Steel (304/304L)5: Typical yield strength1 = 205 MPa.

- Austenitic Stainless Steel (316/316L): Typical yield strength1 = 205 MPa.

- Conclusion: Common structural carbon steels are stronger in yield strength1 than common austenitic stainless steels.

2. Tensile Strength and Ductility:

- Carbon Steels have good ductility (they stretch before breaking).

- Austenitic Stainless Steels typically have higher tensile strength (the stress to break) and excellent ductility, often better than carbon steel. But for structural design, yield strength1 is the limiting factor.

3. Hardness and Wear Resistance:

- Stainless Steels can be harder and more wear-resistant than mild steel in their annealed state. However, carbon steels can be heat-treated to achieve very high hardness.

Why Carbon Steel Wins for Hull Structures:

- Strength-to-Cost Ratio6: This is the decisive factor. AH36 provides 355 MPa strength at a low cost. Achieving similar strength with stainless would require a special, expensive grade and would increase material cost by 500-1000%.

- Weldability and Fabrication7: Carbon steel is easier and cheaper to weld on a massive scale. Stainless steel has different thermal properties, requires more skill, and can suffer from distortion.

- Industry Practice: The entire design philosophy of modern ships is based on welded carbon steel structures. Coatings and cathodic protection effectively manage corrosion.

When Stainless Steel is Chosen (Despite Lower Yield Strength):

Stainless is selected when the primary failure mode is corrosion, not load. A handrail’s job is to not rust away, not to support the weight of the ship. Its 205 MPa yield strength1 is more than enough for that job.

Practical Comparison for a Ship Component:

| Component & Primary Need | Better Choice: MS/Carbon or SS? | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Hull Bottom Plate (needs strength, affordable weight) | Carbon Steel (AH36) | Provides high strength (355 MPa) at a viable cost. Corrosion is managed by coatings. |

| Propeller Shaft (needs strength + corrosion/fatigue resistance) | Special High-Strength Stainless Alloy or Bronze | Must withstand torque and seawater; standard carbon steel would corrode quickly. |

| Deck Cargo Securing Point (needs high strength) | High-Strength Carbon Steel | Strength is key; it is painted for protection. |

| Galley Sink (needs hygiene, corrosion resistance8) | Stainless Steel (304) | Strength is secondary to corrosion resistance8 and cleanability. |

For a rational buyer, the choice is clear: carbon steel for structure, stainless for specific corrosion challenges. This understanding helps clarify which metal is used where in a ship.

Which type of metal is used in a ship?

While steel dominates, a modern ship is a mosaic of different metals and alloys, each chosen for a specific property. Walking through a ship, you’ll see more than just steel. An engineer in a Saudi shipyard once gave me a tour pointing out at least six different metals used in various systems.

The primary metal used in a ship’s hull and main structure is carbon steel1 (specifically marine-grade steel2). Other important metals include stainless steel3 (for fittings and specific systems), aluminum alloys4 (for superstructures to save weight), copper-nickel alloys5 and titanium6 (for heat exchangers), and bronze7 (for propellers and bearings). Each metal is selected based on a balance of strength, weight, corrosion resistance, and cost for its specific function.

A Tour of a Ship’s Material Palette

Let’s look beyond the hull to see where other metals play critical roles.

1. The Backbone: Carbon Steel (Already Covered)

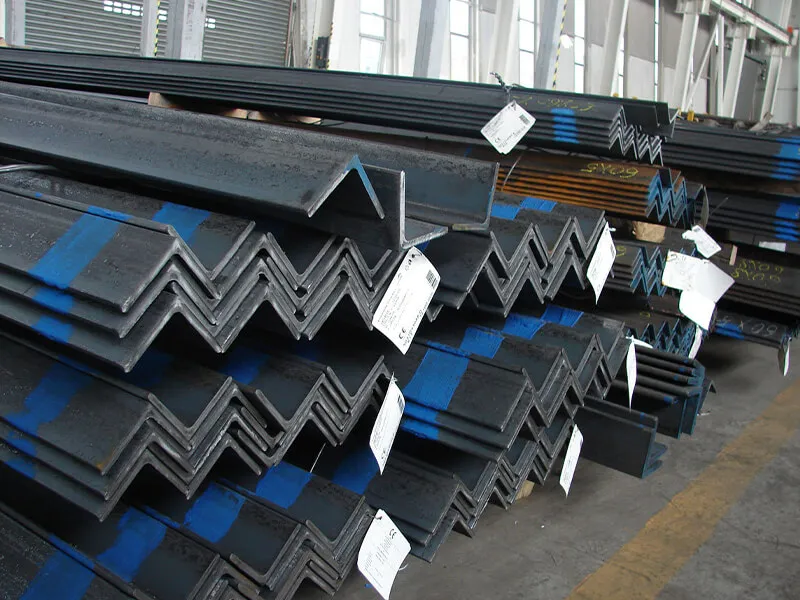

- Forms: Plates, sections (angles, bulb flats), forgings, castings.

- Use: Hull, decks, bulkheads, frames, foundations. Constitutes about 90% of the ship’s structural weight.

2. The Corrosion Fighters: Stainless Steel and Aluminum

- Stainless Steel (304, 316, Duplex):

- Use: Deck railings, ladders, cleats, door hardware, galley equipment, piping for freshwater and some chemicals, exhaust uptakes.

- Reason: Excellent corrosion resistance with minimal maintenance.

- Aluminum Alloys (5000 & 6000 series):

- Use: Superstructures (passenger cabins, bridge wings), lifeboats, interior partitions.

- Reason: Lightweight (about 1/3 the density of steel). Reducing weight high up improves the ship’s stability. It is more expensive and harder to weld than steel.

3. The Seawater Specialists: Copper Alloys and Titanium

Seawater is highly corrosive and causes biofouling. These metals resist both.

- Copper-Nickel Alloys (e.g., 90/10 CuNi, 70/30 CuNi):

- Use: Seawater piping systems, heat exchanger tubes, condenser tubes.

- Reason: Good corrosion resistance, inherent anti-fouling properties (deters marine growth).

- Bronze (Aluminum Bronze, Manganese Bronze):

- Use: Propellers, stern tubes, bearings, valves.

- Reason: Good strength, excellent corrosion resistance, and good casting properties for complex shapes like propellers.

- Titanium:

- Use: Heat exchangers on advanced naval vessels or luxury yachts, where cost is less of an issue.

- Reason: Exceptional corrosion resistance and strength, but very high cost.

4. Other Specialized Metals:

- Zinc (as sacrificial anodes8): Blocks of zinc are welded to the hull. They corrode instead of the steel, providing cathodic protection.

- Lead: Used for sound damping and radiation shielding in certain areas.

Material Selection Matrix for Key Components:

| Ship Component | Primary Metal(s) Used | Key Property Required |

|---|---|---|

| Hull Plating | Marine Carbon Steel (AH36) | High strength, toughness, weldability. |

| Main Deck | Marine Carbon Steel (AH36) | High strength to support cargo. |

| Passenger Cabin Superstructure | Aluminum Alloy | Light weight (for stability). |

| Propeller | Bronze (Ni-Al Bronze) | Strength, corrosion resistance, castability. |

| Seawater Cooling Pipe | Copper-Nickel Alloy | Corrosion and biofouling resistance. |

| Deck Handrail | Stainless Steel (316) | Corrosion resistance, low maintenance, appearance. |

| Engine Crankshaft | Forged Alloy Steel | High fatigue strength. |

| Cathodic Protection | Zinc or Aluminum Anodes | Sacrificial corrosion. |

For a supplier like us, our core expertise lies in the carbon steel1 that forms the ship’s skeleton—the plates, angles, and bulb flats. However, understanding the full material ecosystem allows us to provide better advice to our clients and appreciate the complex engineering behind every vessel that sets sail.

Conclusion

Ship construction relies primarily on specialized marine carbon steel for its hull, chosen for optimal strength and toughness. This is complemented by stainless steel, aluminum, and copper alloys for specific roles where corrosion resistance, weight savings, or seawater compatibility are paramount, creating a vessel optimized for safety, efficiency, and longevity.

Tags: ship construction materials, marine carbon steel, stainless steel in ships, aluminum superstructure, marine metals, hull steel grades, shipbuilding alloys

-

Explore the significance of carbon steel in shipbuilding, its properties, and why it’s the primary choice for hulls. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover the unique properties of marine-grade steel that make it essential for shipbuilding and durability. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about the role of stainless steel in shipbuilding, especially its corrosion resistance and applications. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover how aluminum alloys contribute to ship stability and weight reduction, enhancing overall performance. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Find out how copper-nickel alloys resist corrosion and biofouling, making them ideal for seawater systems. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the exceptional properties of titanium that make it suitable for high-end marine applications despite its cost. ↩ ↩

-

Understand the advantages of bronze in ship components like propellers, focusing on its strength and corrosion resistance. ↩ ↩

-

Learn how sacrificial anodes work to prevent corrosion in ships, ensuring longevity and safety. ↩ ↩ ↩