You are designing the stiffeners for a new container ship’s hull. You can use standard L-angle or bulb flat steel. The angle is cheaper and more common, but the bulb flat offers a hidden efficiency that directly impacts the ship’s profitability and performance.

Marine engineers choose bulb flat steel over L-angle profiles because it provides a significantly higher section modulus and moment of inertia for the same weight. This means superior bending stiffness and strength as a hull or deck stiffener, leading to weight savings, increased cargo capacity, and better fuel efficiency—key economic advantages in ship design.

This is not a minor detail; it’s a fundamental design optimization with multi-million dollar implications over a ship’s lifetime. To understand this choice, we need to look at the bulb flat’s primary role, and also clear up a common confusion about a different "bulb" on ships. Let’s start with the basics.

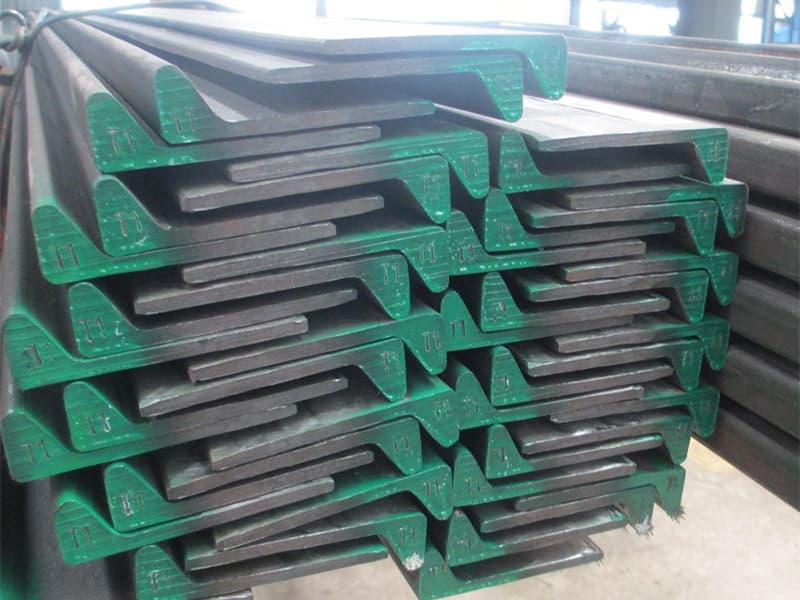

What are bulb flats1 used for?

On a ship’s structural drawing, bulb flats1 have one job. They are not versatile framing members; they are specialized, high-performance components for a specific structural system.

Bulb flats are used almost exclusively as longitudinal and transverse stiffeners. They are welded perpendicular to the hull, deck, and bulkhead plates to form efficient T-beams2. These T-beams2 prevent the large, thin plates from buckling under load and add crucial bending strength to the ship’s global structure.

Think of a ship’s shell as a large, thin metal box. Water pressure wants to crush it, and cargo loads want to bend it. Bulb flats are the ribs that give this box its rigidity. Their design is a direct response to the physics of large-scale bending.

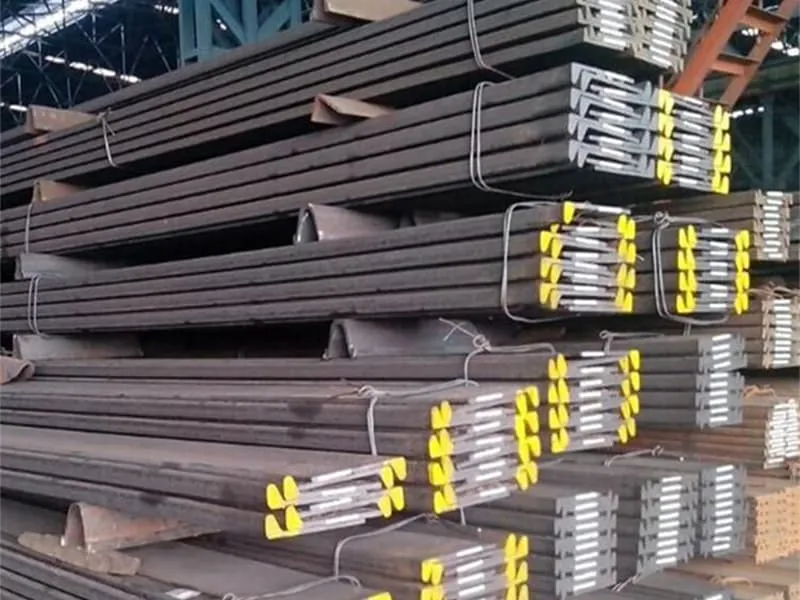

The Engineering Principle: Creating a Composite Beam

When you weld a bulb flat to a plate, you create a composite structural element called a "T-beam."

- The steel plate becomes the wide flange of the beam, handling compression and tension.

- The bulb flat becomes the deep web, providing shear strength and depth.

- The bulb (the rounded tip) is the key innovation. It adds mass at the farthest point from the plate. This dramatically increases the section modulus, which is the geometric property that determines bending strength.

A bulb flat is optimized for this single function. An L-angle, in contrast, is a general-purpose shape good for connections and bracing, but its material is not distributed as efficiently to resist bending in one primary direction.

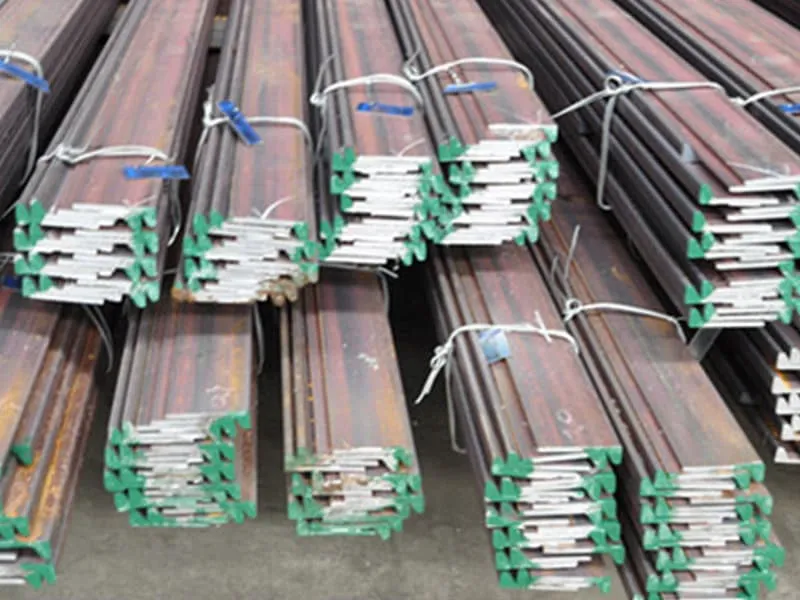

The Performance Advantage in Practice

This efficiency translates into real-world benefits that justify the engineer’s choice:

- Weight Reduction: For the same required stiffness, a bulb flat uses less steel than an L-angle. This directly reduces the ship’s lightweight.

- Increased Cargo Capacity: Every ton saved in the ship’s structure is a ton added to its potential cargo (deadweight). This directly increases revenue.

- Fuel Efficiency: A lighter ship requires less power to move, reducing fuel consumption over its 25+ year lifespan. This is a major operational cost saving.

For these reasons, in areas where the primary load is bending—like the hull bottom under water pressure or the deck under container stacks—bulb flats1 are the undisputed choice. L-angles are reserved for brackets, frames, and connections where multi-directional support is needed. The bulb flat’s application is narrow but critically important to the ship’s core strength and economics.

What are the disadvantages of bulbous bow1s?

This question addresses a common point of confusion. The "bulb" in "bulb flat steel" has nothing to do with a ship’s "bulbous bow1." They are completely different components with different purposes. It’s vital to separate these concepts.

A bulbous bow1 is a hydrodynamic feature on the front of a ship. Its disadvantages include increased construction cost and complexity2, added weight at the bow3, potential damage in shallow water or when docking, and only being fuel-efficient within a narrow range of operating speeds (its design speed).

The bulbous bow1 is part of the ship’s outer hull shape, designed to interact with water. Bulb flat steel is an internal structural member, designed to resist forces. Mixing them up can lead to serious misunderstandings in technical discussions.

The Downsides of a Hydrodynamic Bulb

The bulbous bow1 is a trade-off. It saves fuel at cruise speed by creating wave interference that reduces drag. But this benefit comes with several costs:

- Construction Cost & Complexity: Building and fairing the curved, protruding bulb is more difficult and expensive than a traditional straight bow.

- Added Weight Forward: The bulb adds weight at the very front of the ship. This must be compensated for in the ship’s balance and stability calculations.

- Operational Vulnerability: In port, during docking, or in shallow waters, the bulb is prone to damage from contact with the seabed, quays, or debris. Repair is complex.

- Speed-Specific Efficiency: It is optimized for one "design speed." If the ship operates slower or faster than this (e.g., in slow steaming or when rushing to port), the bulb can actually increase resistance, making it less efficient.

- Not Suitable for All Ships: For ships that operate at highly variable speeds (like tugs, naval vessels, or cruise ships in complex itineraries) or in ice, a bulbous bow1 may be ineffective or a liability.

Bulb Flat vs. Bulbous Bow: A Clear Contrast

Understanding the disadvantages of a bulbous bow1 helps highlight why the bulb flat is such a good choice in its own domain.

| Aspect | Bulbous Bow (Hydrodynamic) | Bulb Flat Steel (Structural) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Reduce wave-making resistance to save fuel. | Increase bending stiffness of plates to save weight and add strength. |

| Location | External, at the front of the ship. | Internal, welded to hull, decks, and bulkheads. |

| Key Disadvantage | Efficiency limited to a specific speed; vulnerable to damage. | Slightly higher initial material cost than simple flat bar; specialized use. |

| Universal Application? | No. Depends on ship type, operating profile, and trade route. | Yes. Used on virtually all large steel-hulled merchant and offshore vessels. |

The bulb flat has none of the operational vulnerabilities of the bulbous bow1. Its "disadvantage" of higher upfront cost is quickly offset by the lifelong weight-saving benefits it provides. While a naval architect might debate the need for a bulbous bow1, they will almost always specify bulb flats for primary stiffening. They are a fundamental, non-negotiable component of modern ship design.

Why do ships use bulbous bows1?

Since we’ve distinguished it from bulb flat steel, let’s quickly address why the bulbous bow exists. This underscores how marine engineering applies specialized shapes to solve specific problems—a theme shared with bulb flats.

Ships use bulbous bows1 for fuel efficiency. The bulb creates its own wave system that destructively interferes with the wave created by the ship’s hull. This reduces overall wave-making resistance, allowing the ship to move through the water using less engine power, especially at its designed cruising speed.

The principle is about managing energy in the water. A moving ship pushes water aside, creating waves. Making these waves consumes a large portion of the engine’s power at higher speeds. The bulbous bow is a clever trick to reduce this energy loss.

The Economic Driver

The sole reason for the bulbous bow’s existence is operational economy2. Fuel is the single largest variable cost for a ship owner. A well-designed bulbous bow can reduce fuel consumption by 10-15% at the design speed. For a large container ship burning hundreds of tons of fuel per day, this saving translates into millions of dollars per year.

This is conceptually similar to why bulb flats are used: for economic efficiency. The bulbous bow saves fuel by shaping water flow. The bulb flat saves weight (which also saves fuel) and increases cargo capacity by shaping steel efficiently. Both are applications of form following function to improve the bottom line. One is a hydrodynamic form, the other is a structural form.

Why doesn’t Icon of the Seas1 have a bulbous bow2?

The [Icon of the Seas](https://www.royalcaribbean.com/cruise-ships/icon-of-the-seas)[^1], the world’s largest cruise ship, is a perfect case study to understand when the bulbous bow2‘s disadvantages outweigh its benefits. Its design choices highlight that not all "bulbs" are applicable in all contexts.

The Icon of the Seas1 likely does not have a traditional bulbous bow2 because its operational profile is unsuitable. Cruise ships operate at highly variable speeds, frequently maneuver in and out of ports, and prioritize passenger space and comfort in forward areas (like theaters or observation lounges) over the hydrodynamic efficiency gained at a single cruising speed.

This example reinforces that the bulbous bow2 is a tool for specific conditions. Its absence on such a prominent vessel teaches us about design priorities.

Analyzing the Design Priorities of a Cruise Ship

A cruise ship’s design drivers are fundamentally different from those of a cargo vessel.

- Variable Speed Profile: A cargo ship on a two-week ocean crossing will travel at a steady "service speed" 95% of the time. A cruise ship’s itinerary involves short hops between islands, slow scenic cruising, and frequent stops. It rarely stays at its maximum speed long enough for a bulbous bow2 to provide net fuel savings.

- Maneuverability and Draft: Cruise ships often visit shallow, pristine ports. A protruding bulb increases the risk of grounding and damage to coral reefs. A simpler, stronger bow is more practical.

- Internal Volume and Layout: The front of a cruise ship is prime real estate for multi-deck theaters, observation lounges, and cabins. A bulbous bow2 protrudes into this space, complicating interior design. A straight bow provides more usable volume.

- Passenger Comfort: Some studies suggest a bulbous bow2 can increase pitching in certain sea conditions. For a vessel where passenger comfort is paramount, avoiding any potential source of motion is a consideration.

The Contrast with Bulb Flat Steel

This case highlights a crucial point: While the bulbous bow2 is optional and situational, bulb flat steel3 is not.

- The bulbous bow2 is a hydrodynamic optimization that can be discarded if other priorities (maneuverability, layout, variable speed) are more important.

- The bulb flat is a fundamental structural necessity. Whether it’s a cargo ship, a tanker, an offshore platform, or even a large cruise ship like the Icon of the Seas1, the hull, decks, and bulkheads still need stiffening. On a cruise ship, you will find extensive use of bulb flats in the lower hull and technical spaces, even if the bow shape is different.

The Icon of the Seas1‘ design confirms that engineers make choices based on the overall mission. They forgo the hydrodynamic bulb because it doesn’t fit the mission. But they cannot forgo the structural efficiency of bulb flats because the laws of physics and economics still apply. The ship still needs to be strong, lightweight, and cost-effective to build, and bulb flats deliver that in a way L-angles simply cannot match for primary stiffening applications. This is why the choice of bulb flat over an L-profile is so consistent across different ship types.

Conclusion

Marine engineers choose bulb flat steel for its unmatched structural efficiency, leading to lighter, stronger, and more profitable ships. This is a fundamental material choice, distinct from the situational use of hydrodynamic bulbous bows, and is driven by core principles of naval architecture and economics.

-

Explore the unique design features of the Icon of the Seas to understand its innovative approach to cruise ship architecture. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about the pros and cons of bulbous bows in ship design to see why they are not always used. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Find out why bulb flat steel is essential in shipbuilding and how it contributes to the structural integrity of vessels. ↩ ↩