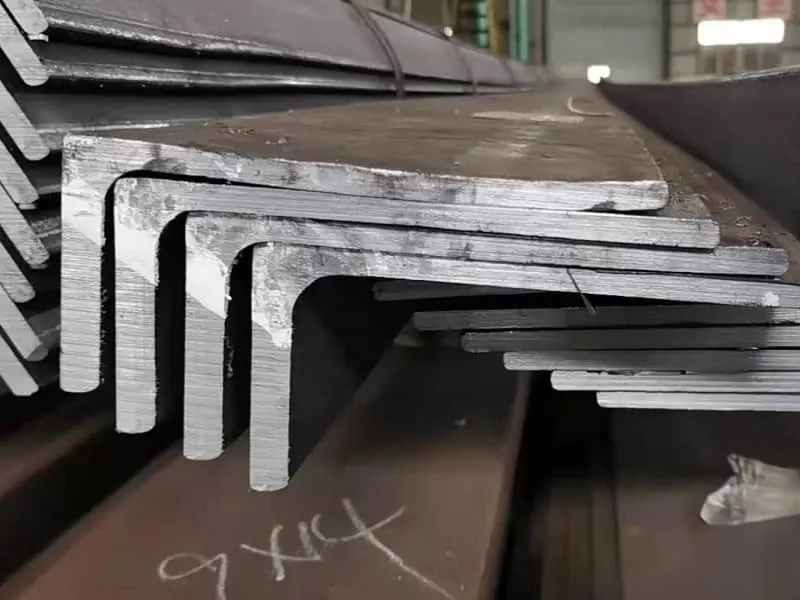

Are you concerned that traditional steel shapes like angle bars are becoming obsolete with new shipbuilding methods? This is a common worry. But in reality, the simple L-section remains as vital as ever.

Marine L sections, or angle bars, are still essential because they provide unmatched strength-to-weight efficiency, ease of fabrication, and versatility. They are fundamental for structural stiffening, framing, and safety features like citadels, proving that robust, proven solutions coexist with modern shipbuilding innovation.

I hear this question often from clients exploring new projects. They see advanced materials and designs, and wonder if the basics have changed. From my daily work supplying these materials globally, I can tell you the foundation hasn’t shifted. The questions we’ll explore next show exactly why the humble L-section is irreplaceable, touching on safety, process, material science, and precise engineering.

Why is it important for ships to have closed areas suitable to be used as a citadel1 when sailing through a high risk area?

Imagine a critical alert: your vessel is approaching a high-risk zone. The crew’s safety and the ship’s security now depend on a pre-planned structural feature. This is not just policy; it’s a physical design requirement where steel is the first line of defense.

A citadel1 is a fortified, secure area on a ship where the crew can retreat during a piracy or security threat. It is crucial because it allows the crew to stay safe, maintain command and control, and summon help while being protected from direct attack, thereby safeguarding lives and the vessel.

The Citadel: Where Structural Steel Meets Security Protocol

The concept of a citadel goes beyond just locking a door. It represents a holistic integration of naval architecture, security protocols, and robust construction. Based on discussions with clients whose vessels transit the Gulf of Aden or Southeast Asian waters, this is a non-negotiable specification.

A citadel1‘s effectiveness depends on several key structural and logistical elements. First, its location and construction are paramount. It is typically designed around the ship’s bridge or an interior machinery control room. The walls, doors, and ceilings must be reinforced to resist forced entry for a specified period, often using additional steel plating and specially framed bulkheads.

Second, it must be a self-contained refuge2. This means it has independent access to communication systems (SSAS – Ship Security Alert System3, satellite phones), emergency power, ventilation, water, and food. The crew can "lock down" the ship’s engines and steering from inside, rendering the vessel practically dead in the water and harder to board.

But here is a key insight from the material supply side: The citadel1 is not built from exotic materials. It is constructed using the same marine-grade steel4 plates and sections, like heavy L-angles5 and bulb flats, that form the rest of the ship’s structure. The difference lies in the design intent and the additional layering.

Consider the role of L-sections here. They are not just for framing. In citadel1 construction, they are critical for:

- Reinforcing Bulkheads: Heavier L-angles are used as stiffeners on the bulkhead plates that form the citadel1‘s walls, making them resistant to bending and impact.

- Securing Doors and Hatches: The frames for armored doors are fabricated from sturdy steel sections to ensure a tight, strong fit.

- Creating Internal Support: The internal structure that supports communication equipment and shelters within the citadel1 relies on this familiar, weldable framing.

Let’s break down the citadel1 requirements versus standard accommodation construction:

| Structural Element | Standard Area Construction | Citadel Construction | Role of L-Sections/Angles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulkheads (Walls) | Standard thickness steel plate for watertight integrity. | Increased plate thickness, often with additional armor or spaced plating. | Heavier, more closely spaced angles are welded as stiffeners to support the thicker plate and resist attack. |

| Doors & Hatches | Standard watertight or fireproof doors. | Ballistic/forced entry-resistant doors with complex locking. | Heavy-duty steel angles form the structural frame for these hardened doors, ensuring they align perfectly and transfer load. |

| Internal Communications | Equipment mounted on standard brackets. | Redundant systems with protected cabling and backup power. | Angles are used to fabricate secure equipment racks and conduits that protect vital cables from being cut. |

| Ventilation | Standard ducting. | Protected or concealable ventilation with emergency shut-offs. | Steel angles frame the protective casings and secure the shut-off mechanisms. |

My direct experience comes from supplying materials for retrofit projects. A client in the Philippines needed to upgrade an older bulk carrier to meet the latest BMP (Best Management Practices6) guidelines for high-risk areas. The project required specific thickness plates and substantial amounts of heavy unequal angles to reinforce a designated citadel1 space. The challenge wasn’t the steel itself, but delivering the exact grades and dimensions on a tight schedule to avoid docking delays. Our ability to source certified materials quickly and provide mill test certificates was as critical to their security upgrade as the design itself. This shows that modern maritime security is built on the reliable supply of traditional, high-quality steel components.

What is the modern ship building process?

You might think modern shipbuilding is dominated by robots and fully automated lines. While automation exists, the process remains a sophisticated ballet of precision blocks, not a continuous assembly line. Understanding this reveals where materials like L-sections fit in.

The modern shipbuilding process is a block construction method1. The ship is designed in 3D, then divided into smaller, manageable steel blocks. These blocks are prefabricated and outfitted in workshops, then transported to a dry dock or slipway for final assembly like giant Lego pieces.

Deconstructing Block Construction: Efficiency from Design to Launch

The shift from traditional "keel-laying" to block construction revolutionized the industry. It allows for parallel work streams, better quality control in sheltered environments, and significantly shorter dock times. From visiting partner yards and supplying them, I see how this method dictates material logistics.

The process starts long before the first steel is cut, with Advanced 3D Design and Planning2. Every pipe, cable tray, and bracket is modeled digitally. This "digital twin" is then sliced into logical blocks, often based on functional zones like a section of the double bottom, a piece of the side shell, or an accommodation module.

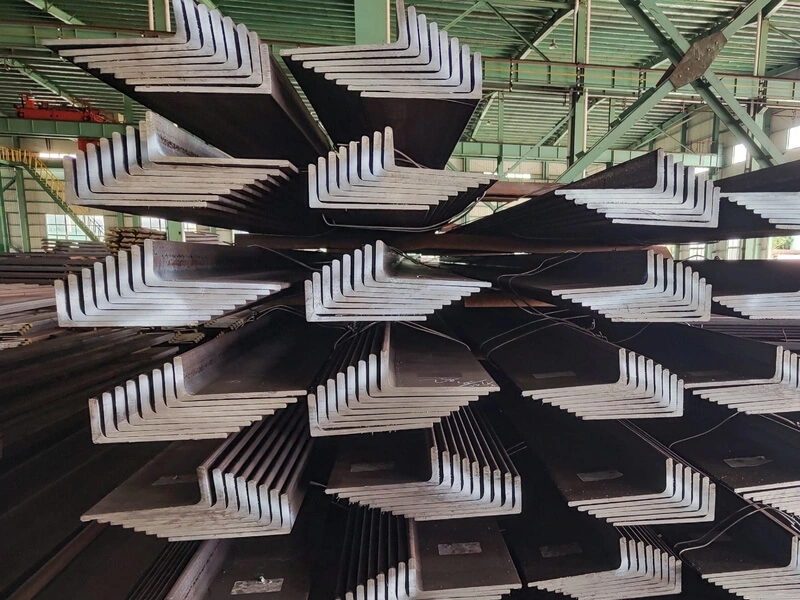

Next comes Block Fabrication in the Workshop3. This is where the steel, including all the L-angles, bulb flats, and plates, arrives. The process follows a clear sequence:

- Panel Line: Large steel plates are welded together to form flat panels. Stiffeners—primarily L-angles and bulb flats4—are then automatically welded onto one side by machines to create stiffened panels for decks, bulkheads, and hull sections.

- Sub-Assembly5: These stiffened panels are joined with other components (like smaller frames or brackets, again made from angles) to form three-dimensional units, like a transverse web frame.

- Block Assembly: Multiple sub-assemblies are joined to form a complete block, which can weigh hundreds of tons. A high degree of outfitting (piping, electrical conduits, insulation) is installed at this stage while access is easy.

Finally, Grand Assembly on the Berth6. The prefabricated and pre-outfitted blocks are lifted by massive cranes into the dry dock. They are aligned with extreme precision and welded together. The final connections of hull longitudinal structures, where bulb flats from one block meet those from the next, are critical welds.

This method places specific demands on the steel supply chain. The table below contrasts old and new methods:

| Aspect | Traditional Sequential Build | Modern Block Construction | Impact on L-Section Supply |

|---|---|---|---|

| Build Sequence | Build from the keel up, adding parts piece by piece on the dock. | Build multiple blocks simultaneously in separate workshops. | Requires steel to be delivered in phased batches matched to multiple block schedules, not one bulk order. |

| Outfitting | Most piping and wiring installed after the hull is complete (outfitting à la carte). | Up to 90% of outfitting done inside the block while it’s accessible (outfitting in the unit). | L-angles for cable trays, pipe supports, and equipment foundations must be supplied early for installation during block fabrication. |

| Quality Control | Inspection happens mostly at the final assembly stage. | Each block can be inspected and tested (e.g., for leaks) in the workshop. | Material certificates (SGS, mill certs) must be traceable to each block for quality records. |

| Dock Time | Very long, as everything is built in place. | Drastically reduced, as only final assembly and welding occur on the dock. | Just-in-time delivery becomes critical to keep each workshop’s production line moving without inventory pile-up. |

My insight here is about synchronization. A yard in Vietnam might be building 20 blocks concurrently for a single container ship. Each block’s fabrication drawings will list hundreds of L-angles of different sizes. If our delivery of a batch of 80x80x8mm angles is delayed for Block 5A (port side shell), it can stall that entire workshop cell. This is why our clients value our reliable logistics from Shandong. We don’t just sell steel; we provide a predictable flow of materials that matches their block construction rhythm, turning their capital-intensive dock into a faster-turnaround asset.

Why is steel commonly used in modern architecture?

Look at any new landmark, from skyscrapers to stadiums. The skeleton is almost always steel. But why has this material, used for centuries, remained the top choice over concrete, aluminum, or composites, especially in the demanding marine environment?

Steel is commonly used because it offers an exceptional combination of high strength, ductility, and versatility at a competitive cost. It can be recycled indefinitely, shaped into almost any form, and its properties can be precisely engineered for specific needs like fire resistance or corrosion resistance, making it the backbone of modern infrastructure.

The Unbeatable Formula: Why Steel Continues to Dominate

The dominance of steel is not an accident. It is the result of a balance of properties that no other material has yet matched in a cost-effective package for large-scale structures. In marine applications, this balance is tested to the extreme, and steel still prevails.

First, consider its Mechanical Properties1. Steel has a very high strength-to-weight ratio. This means you can support enormous loads with relatively slender members, creating more usable space in buildings and larger cargo holds in ships. Its ductility is vital. Unlike brittle materials, steel can bend and deform significantly before failing, providing crucial warning and absorbing energy during events like earthquakes or groundings.

Second, its Fabrication and Construction Advantages2 are unmatched. Steel components can be prefabricated in a factory under controlled conditions, ensuring high quality, and then assembled quickly on-site, reducing construction time. This prefabrication is identical to the shipbuilding block method. The ability to weld, bolt, and modify steel structures with relative ease offers tremendous flexibility for design changes, repairs, and future expansions.

Third, we must talk about Sustainability and Economics3. Steel is the most recycled material on the planet. At the end of a ship’s life (around 25-30 years), over 95% of its steel is recovered and melted down to make new steel. This circular economy aspect is increasingly important. From a project finance perspective, the predictability of steel’s performance and the speed of steel construction reduce financial risk.

For marine use specifically, steel is not just "steel." It is a family of Engineered Alloys4. Ordinary carbon steel would rust quickly in seawater. Marine steel is a different product.

Let’s compare steel to its main alternatives in marine construction:

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages for Primary Hull Structure | Typical Marine Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marine Grade Steel5 | High strength, excellent toughness, good weldability, recyclable, cost-effective for large structures. | Requires protective coatings and cathodic protection to resist corrosion. | Primary hull, decks, bulkheads, frames – the entire main structure. |

| Aluminum Alloy6 | Lighter weight, good corrosion resistance. | Much higher cost, lower strength at high temperatures, difficult welding compared to steel. | Superstructures (to lower center of gravity), high-speed craft, interior fittings. |

| Fiber Reinforced Plastic (FRP)7 | Light, corrosion-free, low maintenance. | Very high material cost for large structures, low modulus of elasticity (flexes more), fire safety concerns, difficult to repair to original strength. | Small boats, patrol vessels, lifeboats, non-structural components. |

| Concrete8 | Low cost, good compression strength. | Very heavy, poor tensile strength (requires reinforcement), brittle, difficult to shape for complex hull forms. | Very limited use; some floating docks or specialized barges. |

My personal take comes from a continuous dialogue with mills. The "steel" we supply today is not the same as 20 years ago. Modern marine steels like AH36, DH36, and EH36 are produced using sophisticated TMCP (Thermo-Mechanical Control Process) technology. This gives them higher strength and better weldability without needing expensive alloying elements. When a client in Saudi Arabia asks for "corrosion-resistant steel," we don’t just send a coated product. We discuss the core grade, the required impact toughness for their operating waters, and then the coating system. The steel itself is the first, and most important, layer of defense. Its inherent, engineered properties are why it remains the unchallenged champion for the primary structure of every commercial vessel afloat.

What is the difference between stringer and stiffener?

Looking at a ship’s structural drawing, you see a web of lines labeled "stiffeners1" and "stringers2." They might look similar, but confusing them can lead to serious design or procurement errors. Their function is defined by direction and purpose.

The main difference is their orientation and primary function. A stiffener is a member attached to a plate to prevent it from buckling, and it can run in any direction. A stringer is a specific type of longitudinal stiffener that runs along the length of the ship, primarily supporting decks and transferring major longitudinal loads.

Direction Defines Function: A Guide to Ship Structural Members

This distinction is fundamental to understanding how a ship’s structure works. As a supplier, we need to understand these terms because they directly relate to the size, grade, and quantity of L-sections and bulb flats3 a client will order.

Think of the ship’s hull as a long, thin box beam bending in the waves. To resist this bending, it needs strong, continuous members running from bow to stern—these are the longitudinal strength members4.

-

Stringers are key players in this system. They are large, continuous longitudinal members. You find them at the edges of decks and along the sides of the ship. A deck stringer5 is a large angle bar or bulb flat that runs where the deck plate meets the side shell. Its job is massive: it ties the deck to the side structure and acts as a major flange for the ship’s overall hull girder, resisting global bending stresses. They are among the most critical and highly stressed components on a vessel.

-

Stiffeners have a more localized job. They support plates against water pressure, cargo loads, or other local forces to prevent buckling. They can be:

- Longitudinal Stiffeners: Run fore-and-aft. On the bottom and deck plating, these are often bulb flats3. On bulkheads, they can be L-angles. When they are part of the primary longitudinal strength system (like bottom longitudinals), they are essentially stringers2 for that specific plate panel.

- Transverse Stiffeners: Run athwartships (side-to-side). These are almost always L-angles or T-sections. They provide support between the larger, heavier transverse frames or web frames.

So, all stringers2 are longitudinal stiffeners1, but not all longitudinal stiffeners1 are important enough to be called stringers2. The term "stringer" is reserved for the primary, heavily loaded members at major structural junctions.

Here is a structural breakdown to make it clear:

| Feature | Stringer (e.g., Deck Stringer, Side Stringer) | Stiffener (General) | Example L-Section Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Global longitudinal strength; connects major structural elements. | Local plate support to prevent buckling. | A large unequal angle (e.g., 200x100x12) is commonly used as a deck stringer5. |

| Orientation | Always longitudinal (fore-and-aft). | Can be longitudinal or transverse. | L-angles are used for both longitudinal and transverse stiffeners6s](https://cnmarinesteel.com/the-manufacturing-process-of-marine-bulb-flat-steel/)[^1] on bulkheads. |

| Size & Importance | Large cross-section, highly stressed, critical to hull integrity. | Smaller cross-section, handles local loads. | Bulb flats are used for primary longitudinal stiffeners1/stringers2 on the hull. L-angles are for secondary stiffening. |

| Location | At major junctions: deck-side shell, bilge, longitudinal bulkhead top. | Attached to any plate panel: deck, hull, bulkhead, shell. | Longitudinal Stiffener: L-angle on a fore-and-aft bulkhead. Transverse Stiffener: L-angle on a transverse watertight bulkhead. |

This practical knowledge directly affects our business. When a new client from Mexico sends an inquiry for "angle bars for stiffeners1," our first question is: "Are they for longitudinal or transverse applications on the hull or bulkhead?" The required size and grade can differ significantly. A transverse stiffener on a non-critical bulkhead might use a commercial-grade angle. A longitudinal stiffener on the side shell, which contributes to global strength, will require a certified marine grade like AH32. By asking the right technical questions upfront, we ensure our clients get the correct, cost-effective material and avoid the risk of supplying under-specified steel. This consultative approach, rooted in understanding these fundamental distinctions, is what builds long-term trust with rational, results-driven buyers.

Conclusion

From securing citadels to forming the backbone of block construction, the marine L-section proves that foundational engineering principles, executed with modern materials, remain essential for safe, efficient, and innovative shipbuilding.

-

Understanding stiffeners is crucial for ship design, as they prevent buckling and ensure structural integrity. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Stringers are vital for supporting decks and transferring loads, making them essential for ship stability. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Bulb flats are commonly used for stringers and stiffeners, enhancing the strength of ship structures. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

These members are key to resisting bending forces in a ship’s hull, ensuring safety and durability. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Deck stringers play a critical role in connecting the deck to the hull, impacting overall ship strength. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Transverse stiffeners provide essential support across the ship, preventing structural failure under loads. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the pros and cons of FRP to see how it stacks up against traditional materials like steel. ↩

-

Understanding concrete’s limitations can help in making informed decisions for marine structure designs. ↩