You need a stiffener for a ship’s bulkhead. You can use a flat bar or an L-angle of the same weight. Choosing the wrong one will make the structure weaker and heavier. The difference is not in the material, but in the shape.

For bending strength, an L-shaped steel angle is significantly stronger than a flat bar of equal weight. The L-shape distributes material away from the neutral axis, giving it a higher section modulus. However, a flat bar can be stronger in pure tension or for simple, short-span applications.

In shipyards from Mexico to Saudi Arabia, I see both profiles used daily. The choice is not random. It is a deliberate calculation based on load type and structural efficiency. Understanding the real strength difference prevents over-engineering and costly mistakes. Let’s dissect each profile, compare their best uses, and clarify a common misunderstanding about steel’s behavior.

What is the strength of flat bar steel1?

A shipyard uses a flat bar as a simple tie rod. It works perfectly. Then they use the same size flat bar as a long, unsupported stiffener. It bends easily. The strength of a flat bar depends entirely on how you load it.

The strength of a flat bar steel1 is defined by its material grade (yield strength, e.g., 235 MPa for Grade A) and its geometric properties. In bending, its strength is low because its material is concentrated close to the neutral axis, resulting in a low section modulus.

When we ask about "strength," we must specify: strength against what? A flat bar can be very strong in one type of loading and very weak in another. Its simple rectangular shape dictates its performance. We need to evaluate its strength in different scenarios.

Evaluating Flat Bar Strength in Different Loading Conditions

| Loading Type | How Strength is Determined | Flat Bar’s Performance | Typical Marine Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tension (Pulling) | Strength = Material Yield Strength x Cross-Sectional Area (A). Formula: F_tension = σ_y * A. | Excellent. All material is equally stressed. A flat bar is very efficient in pure tension if buckling is prevented. | Used as tie rods, small brackets in pure pull, or lap joints where the load is axial. |

| Compression (Squashing) | Strength depends on the material yield strength2 and the slenderness ratio (Length / Radius of Gyration). Prone to buckling. | Poor for long lengths. Its low radius of gyration (r) makes it buckle easily. A short, stubby flat bar can be strong in compression. | Limited use. Only for very short compression struts3 or as part of a built-up column. |

| Bending | Strength = Material Yield Strength x Section Modulus (Z). Formula: M_bending = σ_y * Z. | Very Low Efficiency. For a given cross-sectional area (weight), a flat bar has a very low Z because its height is small and material is near the neutral axis. | Used for minor, short-span stiffening, edge trimming, or backing plates where bending loads are minimal. |

| Shear | Strength = Material Shear Strength x Cross-Sectional Area. | Good. The full cross-section resists shear forces. | Can be used in shear connections4 or as web stiffeners. |

The key takeaway is this: a flat bar is a "one-dimensional" profile. It is excellent for linear, axial loads (tension/compression over short lengths). Its weakness is bending. To increase its bending strength5, you must dramatically increase its height (which makes it thin and prone to buckling sideways) or its thickness (which adds a lot of weight for little gain).

This is why in marine construction6, flat bars have specific, limited roles. They are not used as primary longitudinal stiffeners on hull plates. For that, bulb flats or L-angles are used. A flat bar might be used as a small bracket to reinforce a corner or as a trim piece. When our client Gulf Metal Solutions orders marine steel, they understand these distinctions. Their focus on stable quality means they need the flat bar they receive to have precise dimensions and certified yield strength, so its predictable performance in its intended role is guaranteed.

What is L shape steel?

A designer sees an L-angle as just a bent piece of metal. But in a ship’s frame, that simple bend creates a structural advantage1 that flat bars cannot match. The L-shape is a classic solution for multi-directional strength.

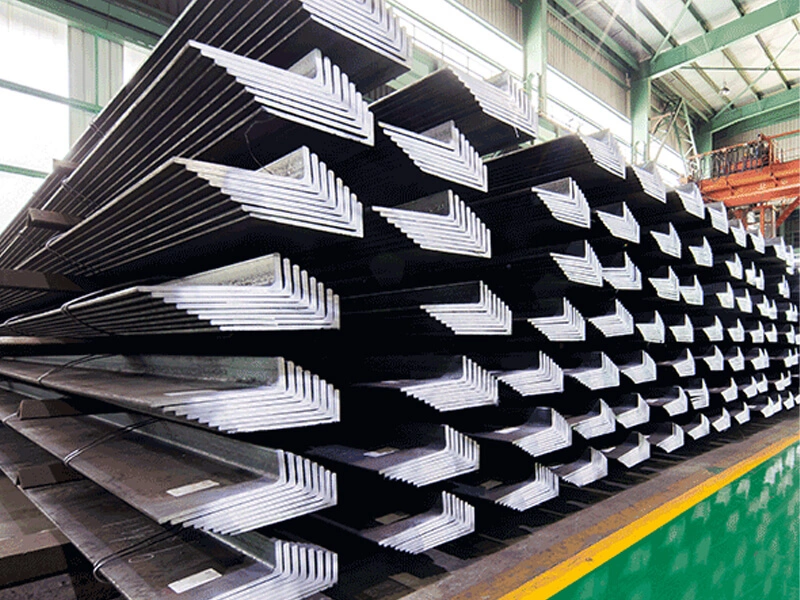

L-shaped steel2, commonly called angle bar3 or angle iron, is a long steel profile with a cross-section forming a 90-degree angle. It has two legs of equal or unequal length, connected along one edge. It provides good strength in two planes and is fundamental for brackets, frames, and stiffeners in marine structures4.

L-shape steel is more than a shape; it is a tool. Its geometry gives it inherent properties that solve common structural problems. Unlike a flat bar, it has two principal axes and can resist loads from multiple directions without additional support.

The Structural Anatomy and Advantages of L-Shaped Steel

| Geometric Feature | Structural Implication | Advantage Over a Flat Bar |

|---|---|---|

| Two Perpendicular Legs | Creates inherent stiffness in two directions (X and Y axes). Can resist forces applied from different angles. | A flat bar is stiff mainly in one direction (against bending in the plane of its height). An L-angle resists bending in two planes. |

| Offset Neutral Axes | The centroid (neutral axis) is located at the intersection of the legs, not at the geometric corner. This places one leg farther from the axis. | This automatically gives the L-angle a higher section modulus5 (Z) than a flat bar of the same weight, making it stronger in bending. |

| Built-in Attachment Flange | One leg can be easily welded or bolted to a primary plate (e.g., a hull plate), while the other leg extends outward to provide stiffness. | It functions as an integral bracket. A flat bar used as a stiffener often requires a separate bracket or welding along its thin edge, which is weak. |

| Good Torsional Resistance | The 90-degree shape provides some resistance to twisting, though it is not as good as a closed section (like a tube). | Better than a flat bar, which has almost no torsional resistance6 and will twist easily. |

The most important advantage is the section modulus5. For example, take an L100x100x10 angle bar3 and a flat bar of the same weight per meter. The flat bar would have to be very wide and thin. The L-angle, with its material distributed along two legs, will have a significantly higher Z value, especially about its strong axis (parallel to one leg). This means it can carry a much larger bending moment before it yields.

In shipbuilding, L-angles are the workhorse for secondary structures. They form the frames of doors, hatch coamings, and ladder stands. They are used as brackets to connect beams to columns. They are used as stiffeners on non-critical bulkheads. Their versatility comes from their shape. When we supply BV or ABS-certified L-shaped steel2, we are providing this versatile, predictable structural component. Fabricators in the Philippines or Romania rely on its consistent dimensions and properties to build these countless sub-assemblies efficiently.

What is the best metal for a flat bar?

A project specifies a "stainless steel flat bar" for a railing. The fabricator uses standard 304 stainless. In a marine splash zone, it rusts within a year. The best metal is not defined by the shape, but by the environment it must survive.

For marine environments, the best metal for a flat bar is the same as for any component: certified marine-grade steel1. For structural applications, use grades like ABS A or AH362. For corrosion resistance in harsh areas, use 316/L stainless steel3. The choice balances strength, corrosion resistance, and cost.

The question often arises because flat bars are used in visible or critical non-structural roles. People think about the metal’s inherent properties, like stainless steel being "rust-proof." But in marine engineering, "best" is always relative to the service condition. Let’s match the metal to the mission.

Choosing the Optimal Metal for Marine Flat Bar Applications

| Application Scenario | Primary Requirement | Recommended Metal / Grade | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Stiffener or Tie Rod (inside hull) | Tensile/Yield strength, weldability, toughness, certification for class approval. | Carbon Steel: BV/ABS/DNV Grade A, B, or AH32 if higher strength is needed. | Cost-effective, strong, and weldable. The full certification (with Mill Certificate) ensures it meets the rules for the vessel’s class. This is non-negotiable for primary structure. |

| Deck Fitting, Rail Base, Exposed Bracket | High corrosion resistance, good appearance, strength. | Stainless Steel: AISI 316 or 316L. | The molybdenum in 316 provides the necessary pitting resistance to salt spray and chlorides. 316L is better for welded parts to avoid corrosion in the weld zone. |

| High-Temperature Area (e.g., near exhaust) | Heat resistance, scale resistance. | Heat-Resistant Steel: Grades like AISI 309 or 310. | Standard carbon steel will oxidize (scale) rapidly. Stainless 316 has temperature limits. Special heat-resistant grades are needed. |

| Non-Critical, Internal Trim or Spacer | Low cost, ease of fabrication. | Mild Steel (Commercial Quality): Like SS400 or A36 (non-certified). | Where classification society rules do not apply, and corrosion is not an issue, a standard commercial grade is sufficient to save cost. |

A critical point is that the "best" structural metal must be certified. A flat bar cut from an ABS AH36 plate is not the same as a rolled ABS AH36 flat bar. The rolling process aligns the grain structure and ensures the through-thickness properties. For certified applications, you must purchase the profile with the proper certification.

This is where our expertise matters. We supply marine-grade flat bars that are rolled to standard dimensions and come with full certification upon request. For a rational buyer focused on results and compliance, this is essential. They cannot use uncertified commercial flat bars in a classed vessel. Our SGS inspection support provides an extra layer of confidence, verifying that the delivered flat bar matches the ordered grade and dimensions. Whether it’s for a simple spacer or a critical tie rod, providing the correctly specified material is part of our value.

Is steel equally strong in tension and compression?

A ship’s deck is in tension when the hull hoggs. The keel is in compression. If steel were weaker in one mode, the ship would fail asymmetrically. Thankfully, for the purposes of basic design, we can assume it is equally strong.

For most structural carbon steels used in shipbuilding, the yield strength1 and ultimate tensile strength are essentially the same in tension and compression. However, long, slender members fail in compression by buckling long before reaching the material’s compressive yield strength1.

This is a fundamental question that confuses many people. The material property2 of steel is symmetric: it resists being pulled apart (tension) just as well as it resists being squashed (compression) at the material level. But a structural member’s behavior is different from a material coupon’s behavior. We must separate material strength from structural strength.

Disentangling Material Property vs. Structural Member Behavior

| Concept | Tension | Compression |

|---|---|---|

| Material Strength (Tested on a small sample) | A test coupon is pulled until it yields. The yield strength1 (σ_y) is measured, e.g., 355 MPa for AH36. | The same test coupon is squashed. The yield strength1 measured is virtually identical to the tensile yield strength1. The stress-strain curve is symmetric. |

| Structural Member Strength (A real column or strut) | A member in tension fails when the stress across its entire cross-section reaches σ_y. Failure is straightforward and predictable. | A long, slender member in compression fails by elastic buckling3 at a stress far below σ_y. The failure stress depends on length, cross-section shape (Radius of Gyration4), and end conditions, not just material strength. |

| Governing Equation | *Tension Capacity: P_tension = σ_y A** (Area). | *Compression Capacity (for slender columns): P_compression = (π² E I) / (K L)²* (Euler’s Formula). This is often much smaller than σ_y A. |

| Implication for L-Angles & Flat Bars | Both profiles are excellent in tension if connections are adequate. Their capacity is simply σ_y times their cross-sectional area. | Both are poor as long compression struts due to low radius of gyration (r). An L-angle buckles easily about its weak axis. A flat bar buckles even more easily. |

This explains why you see very different designs for tension and compression members in a ship’s structure. A tension rod can be a simple flat bar or round bar. A compression strut for the same load would need to be a much larger, bulkier section (like a built-up column from two angles) or a tubular section to increase its radius of gyration and prevent buckling.

For a marine fabricator or designer, this means you cannot simply use a member that is "strong in tension" for a compression role. The shape becomes paramount. This is another reason why L-angles, while better than flat bars, are still not ideal for long compression members unless they are braced or paired. Understanding this principle prevents catastrophic design errors. It reinforces why working with certified materials is not enough; you must also apply them correctly within the principles of structural mechanics5. Our job as a supplier is to provide the material with the guaranteed σ_y. The designer’s job is to ensure the structural shape uses that strength effectively, whether in tension or compression.

Conclusion

Choosing between L-shaped steel and flat bar hinges on the load type. Use L-angles for efficient bending strength and biaxial stability. Use flat bars for simple tension or short-span duties, always selecting the correct marine-grade metal.

-

Understanding yield strength is crucial for evaluating material performance under stress, especially in structural applications. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Understanding material properties is fundamental for selecting the right materials for specific engineering applications. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Exploring elastic buckling helps in understanding failure modes in compression members, essential for safe design. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

The Radius of Gyration is key to predicting buckling behavior, making it vital for structural design. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Grasping structural mechanics principles is essential for engineers to ensure safety and efficiency in designs. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the concept of torsional resistance to grasp its significance in steel design and applications. ↩ ↩