A single bracket with a sharp, unfinished edge can start a crack that leads to a major structural failure. In shipbuilding, the smallest detail, like the edge of an angle bar, is not a minor issue. It is a potential starting point for corrosion, stress, and weld defects.

Proper edge finishing on marine L-shaped steel (angle iron) is critical for safety and longevity. It prevents stress concentration that leads to cracking, improves weld quality by ensuring full penetration, and removes sharp burrs that accelerate corrosion and pose safety hazards to workers.

Many buyers focus only on the steel grade and dimensions. They treat edge finishing as an optional extra. This is a false economy. The edge condition directly impacts fabrication time, final strength, and the structure’s life in a corrosive environment. Let’s examine why this seemingly small detail deserves your full attention.

Why does steel need a finish?

You receive a bundle of steel angles. The edges are rough, with sharp burrs and mill scale1. Your welder must spend hours grinding before he can even start. This wasted labor adds cost and delays your project before fabrication even begins.

Steel needs a finish for three main reasons: protection, performance, and preparation. A finish protects the steel from corrosion2. It prepares the surface for welding or painting. It also ensures dimensional accuracy3 and removes defects that can weaken the final structure or injure workers.

The term "finish" can mean different things. It could refer to the surface condition of the plate, or specifically to the treatment of the edges. For structural sections like L-shaped steel, the edge finish is often more critical than the broad surface finish. Let’s break down the types of finishes and their purposes.

The Purpose of Finishing: More Than Just Cosmetic

A finish is not just about making steel look good. It is a functional requirement that affects the entire fabrication process and the service life of the component. We can categorize finishes into two groups: surface finishes and edge finishes.

Surface Finishes (On the Flat Faces):

- Hot-Rolled (HR) with Mill Scale: The standard, as-rolled condition. The surface has a dark blue/gray oxide layer (mill scale1). This scale must be removed by blasting or grinding before painting to ensure coating adhesion.

- Pickled and Oiled: The steel is dipped in acid to remove mill scale1, then oiled to prevent rust. This provides a clean, uniform surface ideal for further processing or for applications where appearance matters.

- Galvanized: A zinc coating is applied for corrosion2 resistance. Common for exposed structural steel in atmospheric conditions.

Edge Finishes (The Focus for L-Shaped Steel):

This is where most of the functional value lies for fabricators. The standard hot-rolled edge from the mill is often unacceptable for critical work.

- Deburring/Softening: The process of removing the sharp, razor-like burr left after shearing or sawing. An unfinished burr is dangerous to handle and creates a perfect initiation point for corrosion2 and cracks.

- Beveling: Cutting the edge at an angle (typically 30°, 37.5°, or 45°) to prepare for welding. A proper bevel allows the weld to penetrate fully through the thickness of the metal, creating a strong joint. A rough or uneven bevel leads to poor weld quality.

- Grinding/Sanding: Smoothing the edge to a specific roughness. This removes notches and micro-cracks, reducing stress concentration. A smooth edge also allows for better fit-up with other parts.

Consequences of Poor or No Edge Finish:

| Lack of Finish | Direct Consequence | Downstream Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Sharp Burrs | Cuts to workers’ hands. Creates a crevice that traps moisture and starts corrosion2. | Increased safety incidents. Early rust formation under paint. |

| Rough, Uneven Edges | Poor fit-up with mating parts. Gaps must be filled with excessive weld metal. | Longer welding time, higher welding cost, potential for weld defects like lack of fusion. |

| No Bevel on Thick Material | Weld cannot penetrate the full thickness. The joint relies only on surface weld material. | A dramatically weaker connection. High risk of crack propagation from the unwelded root. |

| Mill Scale on Edges | Paint and primers cannot adhere properly to the smooth, glassy mill scale1. | Coating fails prematurely at the edges, the area most vulnerable to damage and corrosion2. |

For marine L-shaped steel, the ideal "finish" from the supplier includes deburred edges and, if specified, cleanly beveled edges ready for welding. This upfront work saves the shipyard countless hours of manual preparation. It is a mark of a supplier who understands the realities of fabrication, not just the sale of raw material.

Does angle iron rust?

You install untreated angle iron as a support in a ship’s bilge. Within a year, you see flakes of brown rust, and the metal loses thickness. The answer is obvious, but the real question is how fast and where it starts.

Yes, angle iron rusts1. Like all carbon steel, it reacts with oxygen and water to form iron oxide (rust). In marine environments2, the presence of salt dramatically accelerates this process. Rust starts fastest at sharp edges, weld points, scratches, and areas where moisture is trapped.

Knowing it rusts is not helpful. You need to know the specific factors that control the rusting process in angle iron. This knowledge lets you choose the right material and specify the right preparation to fight it effectively.

The Corrosion Attack on Angle Iron: Why Edges are the Weakest Link

Rust does not attack a piece of angle iron uniformly. It exploits weaknesses. The geometry of an L-shaped section creates several inherent vulnerabilities that you must address.

The Accelerating Factors in Marine Environments:

- Galvanic Corrosion3: If the angle iron is connected to a more noble metal (like bronze or stainless steel), it will corrode faster as it acts as a sacrificial anode.

- Crevice Corrosion4: The 90-degree interior corner of the angle is a natural crevice. Saltwater and debris can get trapped there, creating an oxygen-depleted zone that accelerates localized corrosion.

- Stress Corrosion Cracking5: If the angle is under constant tensile stress (like in a loaded bracket) and exposed to seawater, cracks can initiate and grow.

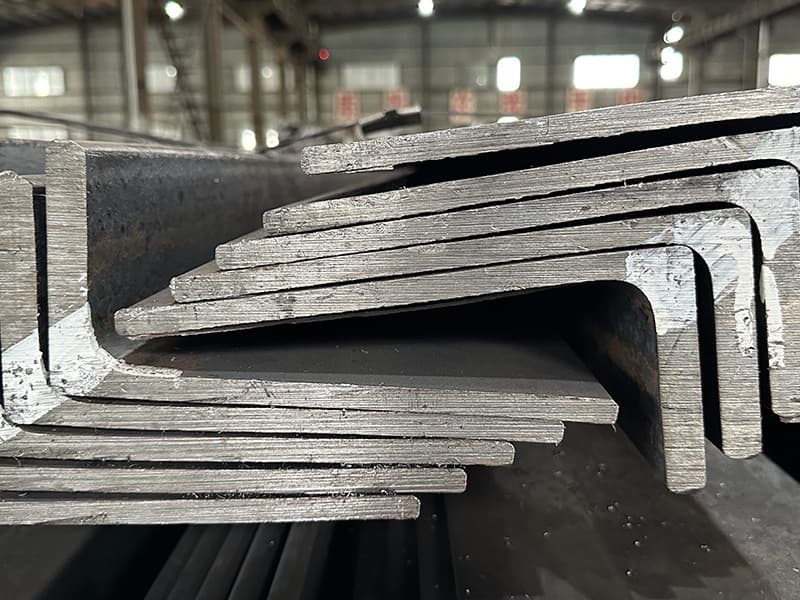

Why Edges Rust First and Fastest:

The edges of angle iron are the epicenter of corrosion for three physical reasons:

- High Surface Area to Volume Ratio6: The thin edge has a lot of surface exposed relative to its mass. This means corrosion has less material to eat through to cause significant thinning.

- Stress Concentration: Sharp corners and burrs are points of high residual stress from the rolling or cutting process. These stressed areas are electrochemically more active and corrode preferentially.

- Poor Coating Coverage: It is very difficult for protective coatings (paint, galvanizing) to build up and adhere properly on a sharp edge. The coating tends to be thin and can easily be chipped off during handling.

The Role of Edge Finishing in Corrosion Prevention:

Proper finishing directly counteracts these vulnerabilities:

- Deburring and Rounding7: Removing the sharp edge eliminates the point of highest stress and creates a smoother surface for coatings to adhere to uniformly. A slightly rounded edge holds a coating much better.

- Cleaning: A finished edge is typically free of mill scale, oil, and debris, providing a clean substrate for primer.

- Creating a Defensible Shape: A smooth, beveled, or rounded edge presents no traps for moisture and gives coatings a fighting chance.

Consider two scenarios for a bracket made from marine angle iron:

| Scenario | Edge Condition | Corrosion Protection Applied | Likely Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| A (Poor Practice) | Sharp, as-rolled edges with burrs. Mill scale present. | Painted directly over mill scale and sharp edges. | Coating fails at edges within months. Rust starts in crevices and under burrs. Rapid section loss begins. |

| B (Best Practice) | Edges deburred and lightly rounded. Mill scale removed by blasting. | High-performance epoxy primer and topcoat applied to clean, profiled surface. | Coating remains intact for years. Corrosion is delayed significantly. The bracket achieves its design life. |

The choice of base material also matters. Using marine-grade angle iron8 (e.g., AH36 grade) provides better inherent resistance than generic mild steel because of its cleaner chemistry and controlled processing. Combining the right material with proper edge finishing is the winning strategy against rust.

What is angle iron1 used for?

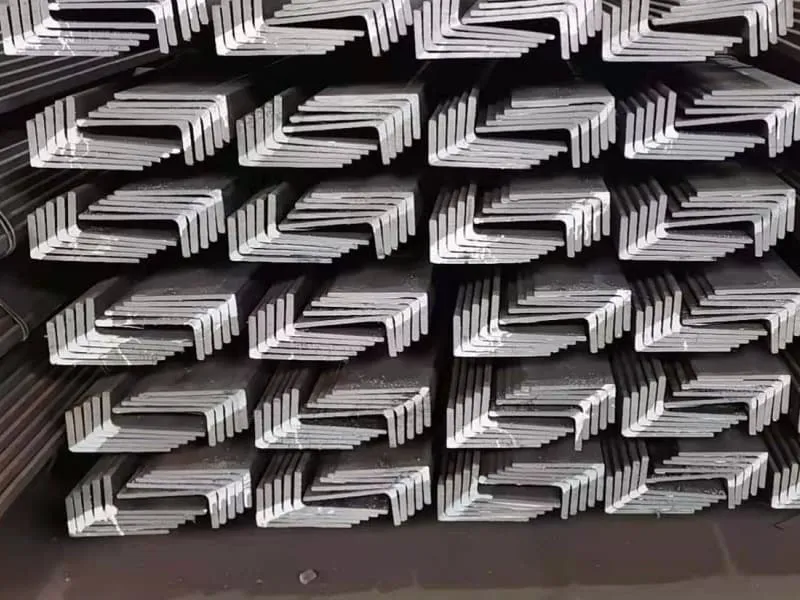

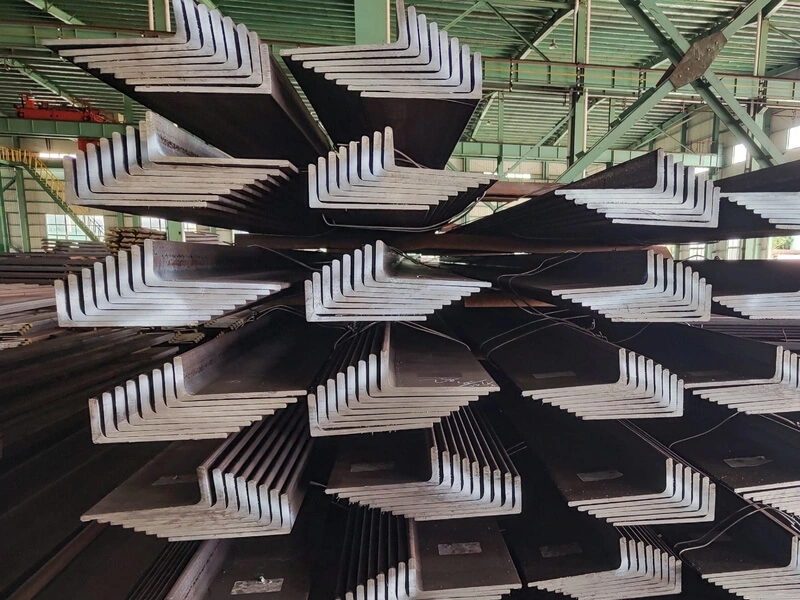

You walk through a ship under construction. You see metal frames, supports, and brackets2 everywhere. Many of these are made from angle iron1. Its simple shape makes it one of the most versatile and essential building blocks in marine construction3.

Angle iron, or L-shaped steel, is used for structural framing4, bracing, brackets2, supports, and stiffeners. In shipbuilding and marine structures, it forms frames, supports decks and bulkheads, creates reinforcement around openings, and is used for countless fabrication5s like ladders, handrail posts, and equipment foundations.

Its use is so common that it can be taken for granted. But not all angle iron1 is the same, and its application dictates the required quality level. Let’s categorize its uses from non-critical to highly critical.

The Workhorse of Fabrication: A Taxonomy of Angle Iron Applications

Angle iron’s strength comes from its geometry. The "L" shape provides good strength in two directions while remaining easy to cut, weld, and bolt. We can divide its marine applications into three tiers of criticality.

Tier 1: Primary and Secondary Structural Members

These are parts where failure would compromise the integrity of the vessel or structure.

- Ship Frames and Stiffeners: Smaller vessels or specific areas may use angles as frames or stiffeners attached to the hull plating.

- Brackets (Knees): The most critical use. Brackets connect beams to frames, decks to bulkheads. They transmit large loads and experience high stress. The weld quality6 here is paramount, which depends heavily on edge preparation.

- Major Support Girders: Angles can be welded together to form built-up I-beams or box sections for heavy support.

Tier 2: Non-Structural but Important Fabrications

These parts are essential for function and safety but are not primary load-bearers.

- Ladders, Staircases, and Walkways: Angles form the stringers and steps.

- Handrails and Guardrails: The upright posts and top rails.

- Equipment Foundations and Mounting Frames: For pumps, valves, generators, and control panels.

- Reinforcement Around Openings: Strengthening the edges of doors, hatches, and manholes in decks and bulkheads.

Tier 3: General Fabrication and Temporary Work

- Work Platforms and Scaffolding during construction.

- Storage Racks and Shelving within workshops or store rooms.

- Jigs and Fixtures used to hold parts during welding.

Implications for Sourcing and Preparation:

The tier of application directly informs the specifications you need from your supplier.

| Application Tier | Required Steel Grade | Criticality of Edge Finish | Why Finish Matters Here |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1: Structural | Certified Marine Grade (e.g., ABS AH36). Must have full MTC. | Very High. Edges often need precise beveling. | Ensures full-penetration welds for maximum strength. Removes stress risers in high-fatigue areas. |

| Tier 2: Functional | Marine grade or good quality commercial steel. | High. Deburring and cleaning are essential. | Improves weld quality6 and coating durability for long-term service. Ensures safety (no sharp edges). |

| Tier 3: General | Standard commercial quality steel. | Moderate. Basic deburring for safety is sufficient. | Mainly for worker safety and ease of handling. |

For our clients like Gulf Metal Solutions, who supply project-based fabricators, understanding this tier system is key. They need to provide the right angle iron1 for the job. For a critical bracket (Tier 1), they will order AH36 angle with beveled edges from us. For a handrail (Tier 2), they might choose a standard grade but still insist on clean, deburred edges for better galvanizing or painting. This tailored approach is what professional procurement looks like.

What is L-shaped metal called?

You are reading a technical drawing. It calls for an "L 150x100x10." Your purchasing agent searches for "angle iron." The workshop manager asks for an "L-profile." The welder calls it an "angle bracket." This confusion can lead to ordering errors.

The standard industrial name for L-shaped metal is Angle Steel1, Angle Bar2, or L-section3. In technical specifications and engineering drawings, it is denoted by the letter L followed by dimensions (e.g., L 100x100x10 means equal legs of 100mm, 10mm thick). The term "angle iron" is a common, traditional name for the same product.

While the names are often used interchangeably, the specific terminology can indicate the material, standard, or context. Using the correct name in communication with suppliers and fabricators prevents misunderstandings. Let’s clarify the nomenclature.

Decoding the Names: From Angle Iron to L-Section

The evolution of terms tells a story about the material and its uses. Understanding these terms helps you communicate precisely in a global industry.

1. Angle Iron: The Traditional Term

- Origin: Dates back to when ferrous metals were wrought iron. The term stuck even after steel replaced iron.

- Connotation: Often implies a hot-rolled carbon steel4 product. It is a general, informal term. In some contexts, it can sound less precise than "angle steel."

2. Angle Steel1 / Angle Bar2: The Standard Industrial Terms

- Usage: These are the preferred terms in modern metal distribution, engineering, and procurement. They are precise and material-neutral (steel).

- Specification: When you say "Angle Steel1," you typically refer to a product made to a formal standard like ASTM A365 (general construction) or ASTM A709 (bridges). For marine use, it would be "Marine Angle Steel6l](https://endura-steel.com/uses-of-steel-angle/)[^1]" to a standard like ABS AH36.

3. L-Section, L-Shaped Steel, L-Profile: The Geometrical Descriptions

- Usage: Common in engineering drawings, CAD software, and architectural contexts. "L-section3" is very clear about the cross-sectional shape.

- Advantage: This term avoids confusion with other types of "angles" (like angular measurement). It is universally understood in technical communication.

4. Unequal Angle: A Critical Subcategory

- Not all angles have equal legs. An L 150x100x12 has one leg 150mm long and the other 100mm long. This is an unequal angle. It is crucial to specify this correctly, as its mechanical properties differ from an equal angle.

How to Specify Correctly and Avoid Errors:

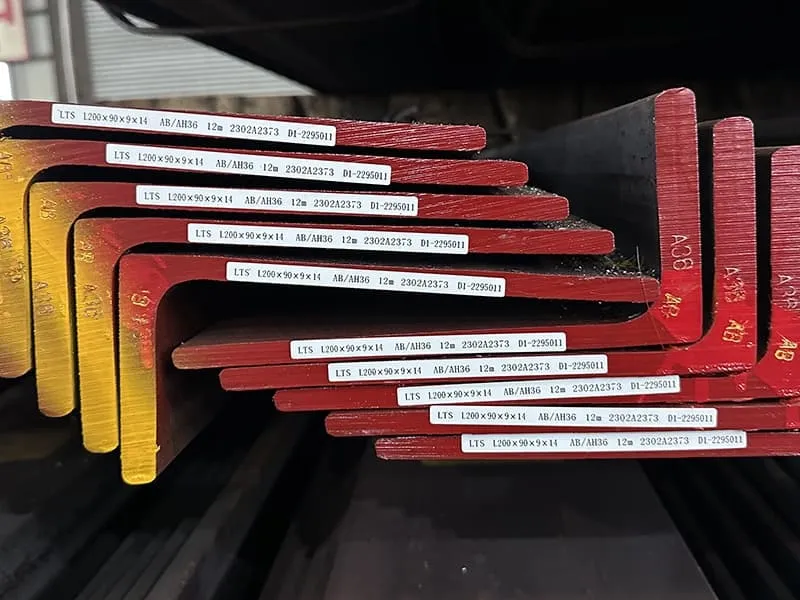

A precise specification leaves no room for guesswork. It should include:

- Name/Shape: Angle Bar2, L-Section.

- Dimensions: Leg Length A x Leg Length B x Thickness (in mm or inches). Example: 100 x 100 x 10mm (Equal) or 150 x 75 x 8mm (Unequal).

- Material Grade/Standard: ASTM A365, EN 10025 S355JR, or ABS AH36 for marine.

- Length: Standard random length (e.g., 6m, 12m) or a specific cut length.

- Edge Finish (If required): "Deburred edges" or "Edges beveled at 37.5°."

Example of a Complete Order Description:

- Vague (Leads to Problems): "We need 5 tons of 4-inch angle iron."

- Precise (Ensures Correct Delivery): "Please quote for 5,000 kg of Marine Angle Steel6l](https://endura-steel.com/uses-of-steel-angle/)[^1], L 100x100x10mm, material ABS AH36, length 6 meters random, with deburred edges."

As a supplier, we see the precise orders from professional buyers. They use terms like "Marine Angle Steel6l](https://endura-steel.com/uses-of-steel-angle/)[^1], ABS Grade" and specify edge condition. This clarity allows us to provide exactly what is needed, ensuring the material is fit for purpose from the moment it arrives at the fabrication yard. This attention to detail in naming and specification is part of delivering a complete, reliable product.

Conclusion

The edge finish on marine L-shaped steel is a small detail with a major impact on weld quality, corrosion resistance, and structural safety, making it a critical factor in procurement and fabrication.

-

Explore this link to understand the applications and benefits of Angle Steel in various construction projects. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

This resource clarifies the distinctions between Angle Bar and Angle Iron, helping you choose the right material for your needs. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn about the significance of L-section in engineering and how it impacts design and construction. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Discover the properties and applications of hot-rolled carbon steel, a common material in construction. ↩ ↩ ↩

-

This link provides detailed specifications of ASTM A36 steel, essential for understanding its applications in construction. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Explore the unique properties and uses of Marine Angle Steel, crucial for marine construction projects. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

-

Learn how proper edge finishing techniques can significantly enhance corrosion resistance. ↩

-

Discover the advantages of marine-grade angle iron for better performance in corrosive environments. ↩